Katharina Gruzei

Bodies of Work

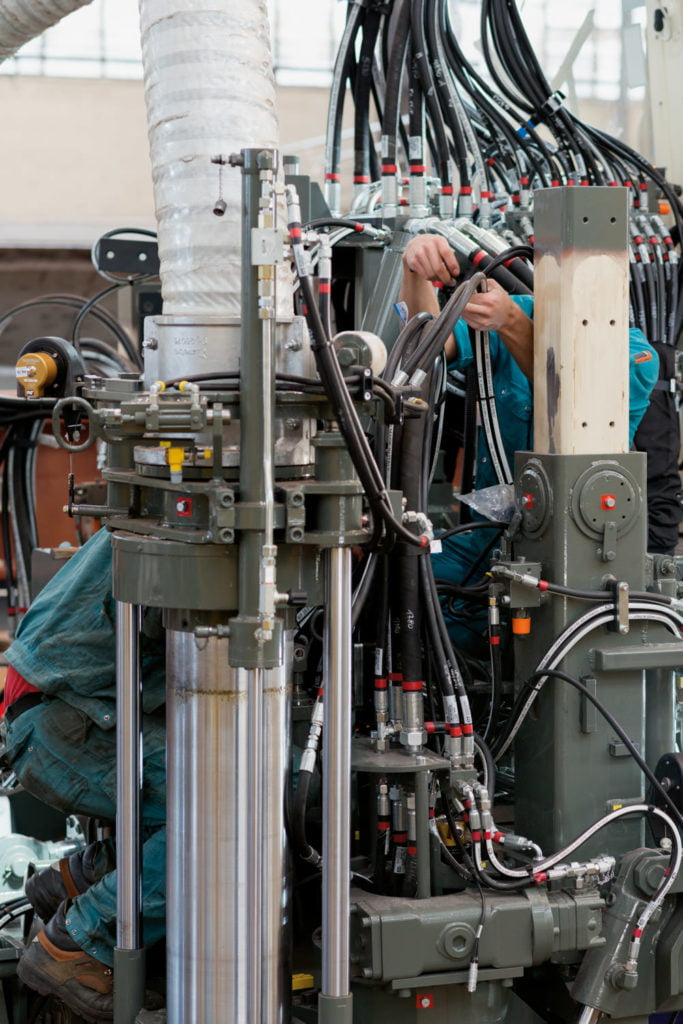

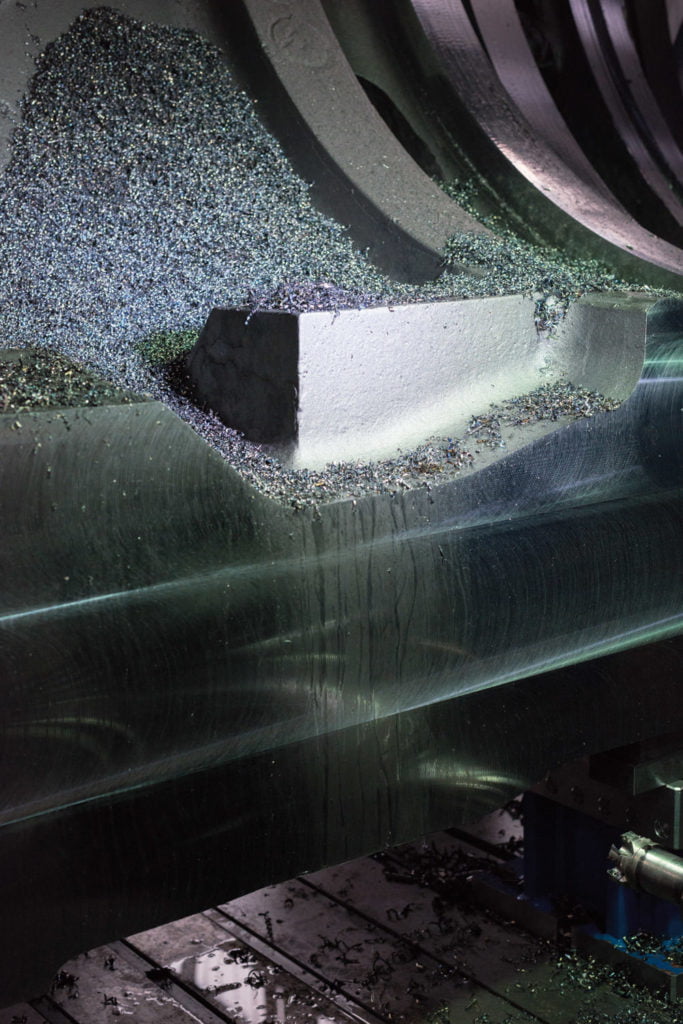

The photo series Bodies of Work was created at the Linz shipyard (ÖSWAG). Over a period of two months I kept a photographic record of working life at the company and documented among others the construction of a new ferry. I would often join the workers as they began their early morning shift and accompany them throughout their working day. I took photographs at night and at weekends when the workshops were deserted and the shipyard was transformed into a nature reserve along the Danube, a haven for mariners and wildlife alike. The sensuality of the location is remarkable even on weekdays when the noise of machinery echoes about the large workshop, metal dust glistening in the air and the stench of hot metal fuming through the air.

Whenever the start and the end of the work breaks were signalled by the works siren, I found that the location’s anachronistic character was amplified even more, a character created by the manual labour performed on the ships and the close ties between man and machine. Similarly, the shipyard also allowed me to leap forward into the future, the ship’s hull viewed from an elevated perspective conjuring up notions of sci-fi space ships, their designs forever inspired by those of the manufacturing industry. Welders in their protective clothing transform into astronauts, their air supply pumped into their helmets via long tubes. Theirs is the working body about which topical debates and discourses are conducted on the significance and transformation of labour. And it is not least the similarity of that high-tech working body with the image of the cyborg that raises ethical questions which, today more than ever before, are linked with the issue of labour as a result of migratory flows and the relocation of industry to low-wage countries. Under what conditions is work now carried out or allocated?

Indeed, the protective clothing worn by the workers is a reminder of the vulnerability of the human body itself and therefore of the utopian fantasy of getting machines, robots and, in future, cyborgs to perform that work. The bodies of the exclusively all-male workforce in those workshops are largely covered up for their own protection. And the naked nymphs on the calendars among the sparks and the flying metal shavings seem almost impregnable – and therefore just as otherworldly.

Katharina Gruzei

I am most grateful to Reinhard Suppan for his open-minded attitude and for the opportunity to realise this project on his company premises. I would particularly like to thank Franz Opolzer, who was very supportive as I went about my photographic work; in fact, many of the photographs would not have been possible without his assistance. And my thanks also to Franz Biermeier for his support and for showing me around the shipyard, and to all those who were kind enough to let me photograph them.

Katharina Gruzei, born 1983 in Klagenfurt; lives and works in Linz and Vienna. Studied Fine Art at the Class for Experimental Design and Study of Cultural Science at the University of Arts and industrial Design Linz.

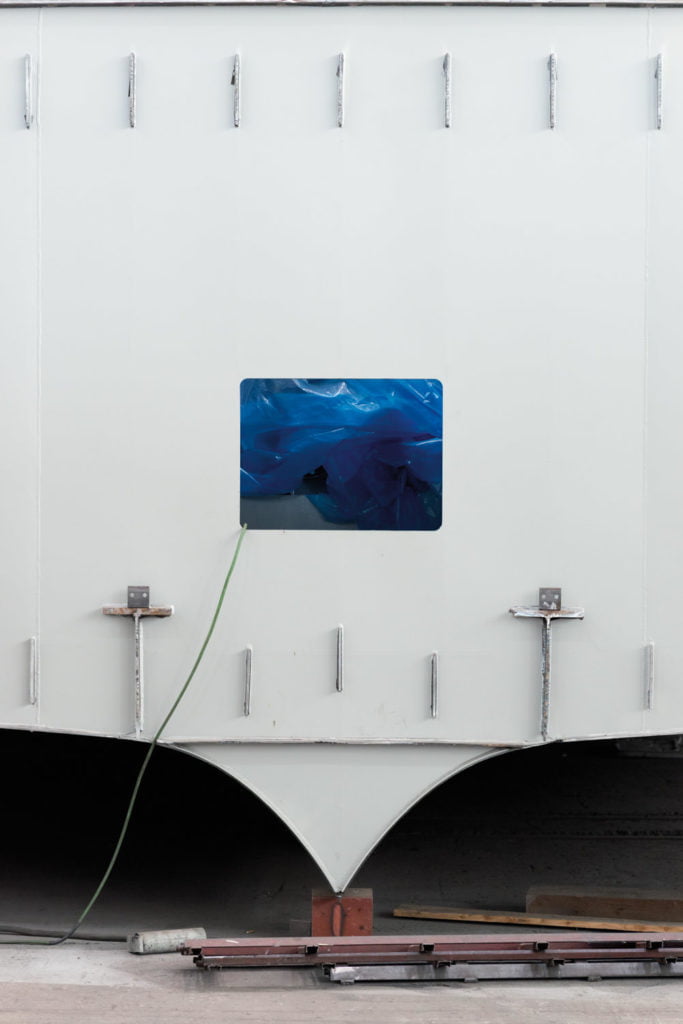

In terms of physics, work equals force times distance, and power is defined as

work per unit time. Two months is the unit of time that elapsed between the two photographs of a ship’s hull that also represent a starting point and a finishing point for Katharina Gruzei’s photo series entitled Bodies of Work. The work performed both industrially and manually lies between the pictures, made perceivable to the senses through the visible changes in the workpiece.

For all the high-tech production processes involved, there is still ‘proper’ work being done at the Linz shipyard[ref]Österreichische Schiffswerft AG (ÖSWAG) was founded by Ignaz Maier in 1840 and looks back at an eventful history lasting more than 170 years; today, it is the last Danube shipyard of its kind in Austria. Besides renovation and repair work it still builds new passenger ships and river ships for inland waterways and rivers. ÖSWAG consists of the shipyard proper and a mechanical engineering firm.[/ref] where the series was created. Hard physical labour, dirt, dust, sweat, shavings and filings: here the clinically meticulous world of full computer- controlled automation has not yet taken over completely, an aspect that was of significance to the artist from the moment she began working on her concept. The title deliberately alludes to two different levels of meaning. Bodies of Work is to be understood not just in the sense of a complex of works, a body of work, a workpiece, but also as a ‘working body’: It is about the human body (in this instance exclusively male) that performs the work, embedded in an industrial environment. Gruzei’s focus is trained not just on the classic relationship between man and machine. She depicts actual work situations, often melding the human body with the mechanical, apparatus- based body to evoke hybrid beings, cyborgs, and astronauts. Gruzei’s sensitive image concept is not aimed at glorifying industrial technology or hero-worshipping the working body. Kitted out in protective working gear designed to ensure their safety, these ‘working bodies’ seem strangely fragile, at times even insecure, almost lost among these oversized machine parts.

A river cruiser pulled ashore for repairs seems to fade into the autumn mist like a phantom ship, mirrored only in the gently lapping waters of the Danube. In the photographs that opens the photo series, that same ship appears utterly radiant, like a shimmer of hope, contrasting with the darkness of the shipyard workshop that provides the architecture framework. The workshop, built in the 1970s as shipbuilding flourished, seems porous and brittle: a symbol of the changing industrial work environment and its socio-cultural and socio-political aspects.

Gabriele Hofer-Hagenauer is the director oft the collection for photography and curator for modern and contemporary art at the Landesgalerie Linz at the Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum.