Manfred Willmann

Work and Recollection

My grandfather, the basket weaver

My tailor

My car mechanic

My watchmaker

Our butcher, who runs a cinema

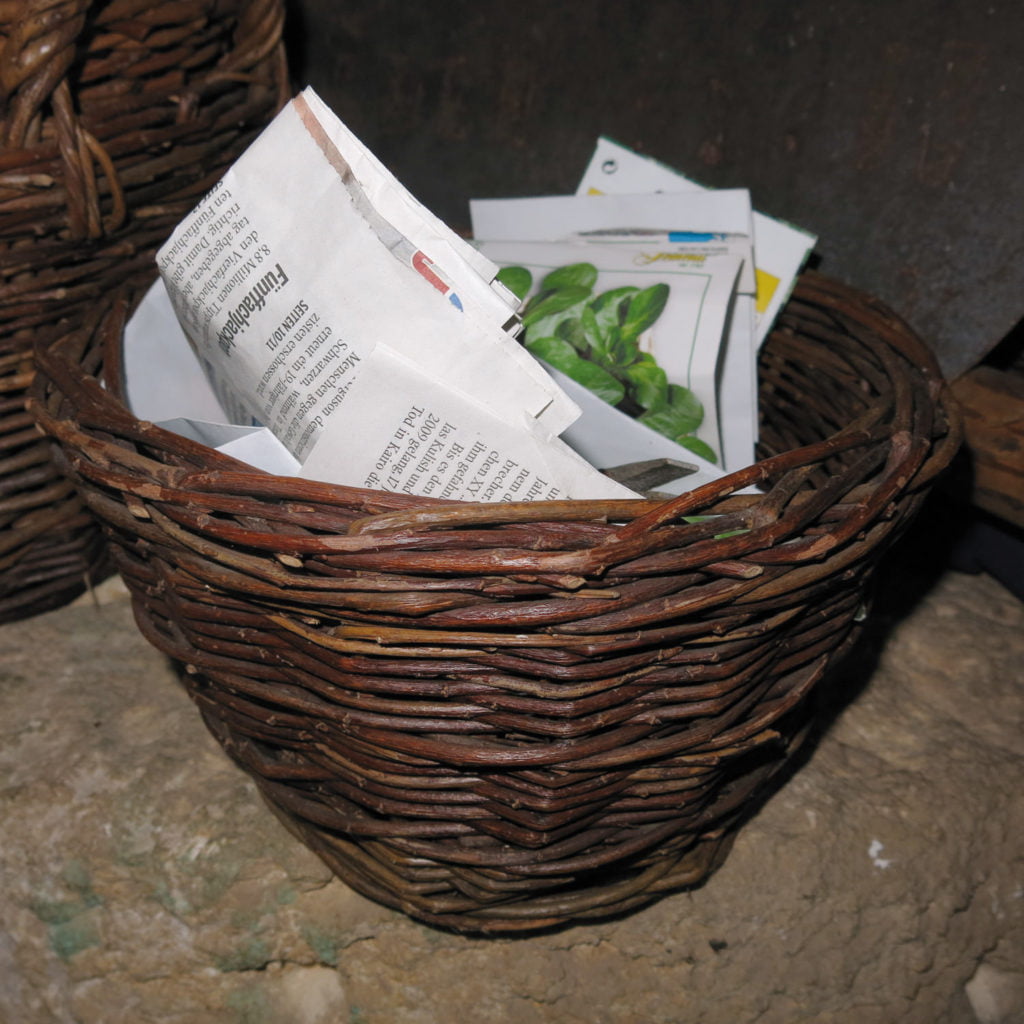

My grandfather, the basket weaver

My grandfather on my father’s side was born in Hodschag/Odžaci, a German-speaking enclave in present-day Serbia, in 1887. In summer 1944, during the Second World War, the family had to leave its home town and finally ended up in Austria. A similar fate also befell my mother’s family: they too were Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) from the same region. Both families had been farmers for many generations. Their lives changed after they resettled in Austria, and yet both generations that lived together in our house continued to live just as they had previously as farmers. My grandfather’s favourite occupation was basket weaving. Our house was full of baskets of all sizes used for all sorts of purposes. He even ended up teaching basket weaving at a nearby agricultural college. At secondary school I made a small plasticine head, a portrait of my grandfather. I have fond memories of watching him and his hands as they worked, and hearing the gentle tapping sound of the willow switches against the lampshade in the kitchen.

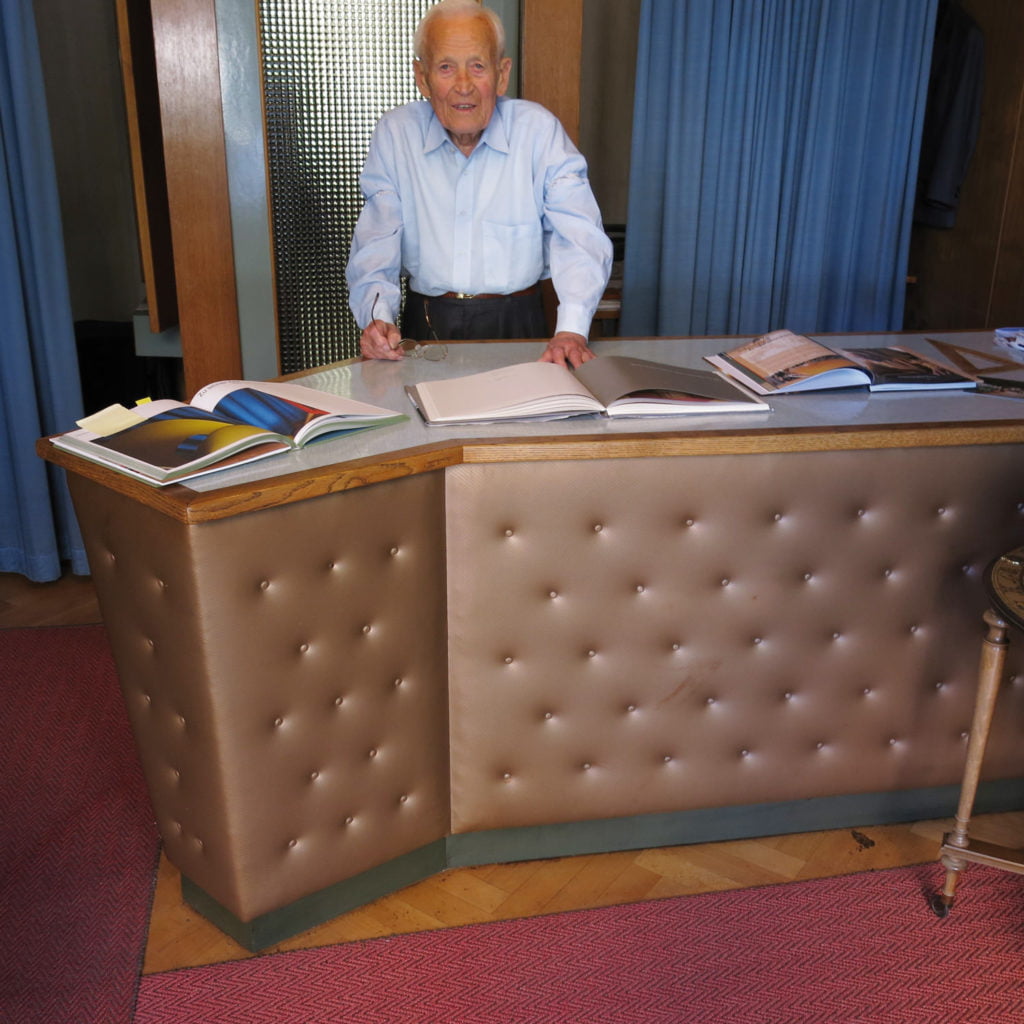

My tailor

I made the acquaintance of Herr Bernschütz in 1980 as I was keen to know if he could make me a suit from a bolt of hand-woven linen. I noticed at the time that he had a slight accent, one that reminded me of the way my parents spoke, and indeed he told me that he, too, originally came from the former Yugoslavia and had come to Austria during the war. Herr Bernschütz opened his tailor’s workshop in 1952 and quickly earned a good reputation. He even had customers travel down from Vienna, and for many years he employed up to seven people. In 1958 he commissioned Karl Hütter, a well- known Graz architect, to design an elegant shop interior for his business premises, and to this day the fittings and furnishings are kept immaculate. He was also an active sportsman, running the New York marathon at the age of 78. Since our first meeting I have had a number of suits and jackets made by him, which I still wear to this day. Herr Bernschütz is now 92. He has been unable to find a successor to take over his workshop and, even though he still goes to his shop every day and changes his display window according to the seasons, there is little hope that these elegant premises and his craftsmanship will survive.

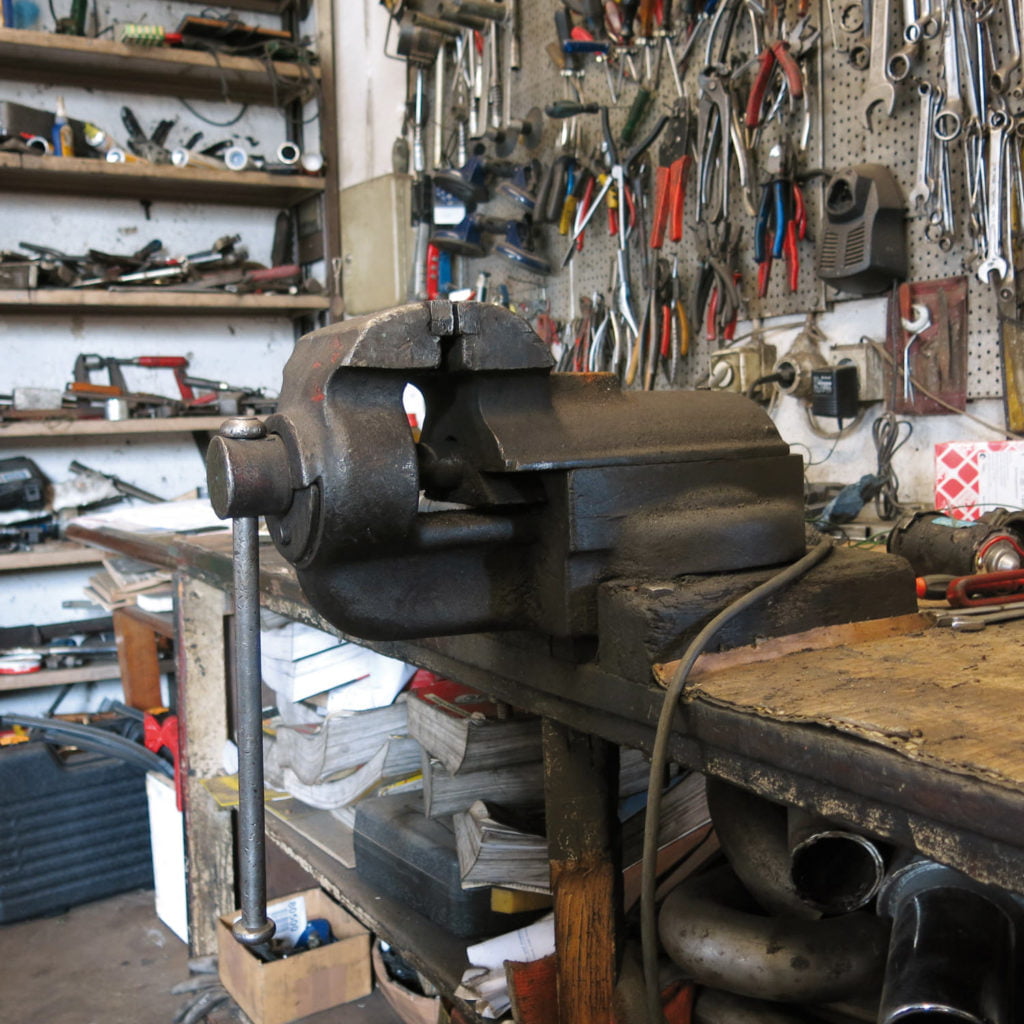

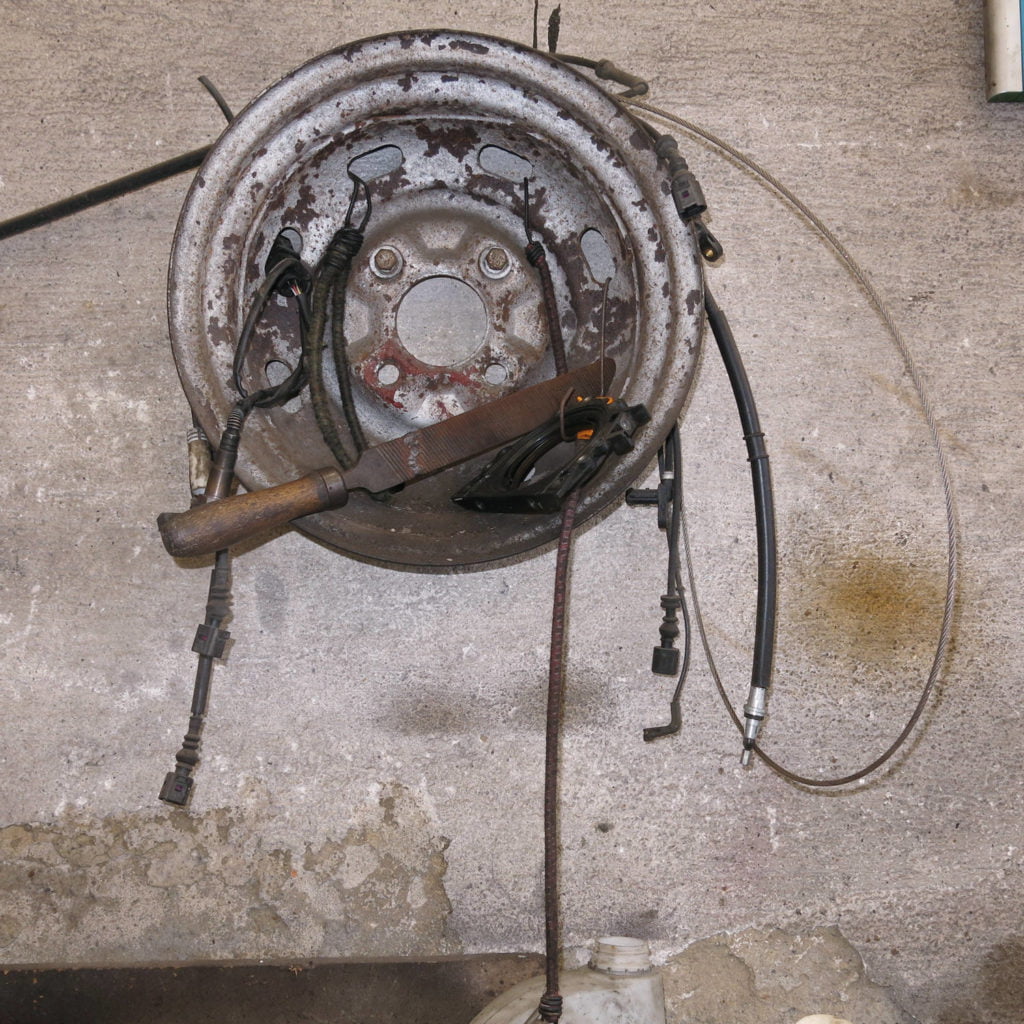

My car mechanic

Cars plays a certain role in my life. For purely sentimental reasons, because of their beauty or the memories associated with them, I’ve owned a number of old cars and occasionally I drive them – when they’re running. Calling in at my car mechanic’s garage is often an urgent necessity, but at the same time it’s always an enjoyable affair. Two people work in this small workshop: the owner and the mechanic, who’s a real expert in vintage cars. Both are enthusiastic car collectors. Horst, the mechanic, also makes sculptures out of unusable car parts. The garage is located on the outskirts of Graz, in what was once agricultural land but is now slowing becoming an industrial zone, not far from the airport. It’s something of a rallying point for car owners who share a fascination and a passion for cars with the two people responsible for all the repairs and servicing work.

My watchmaker

Herr Grubmüller runs his small watchmaker’s workshop, which is also his shop, in Eibiswald; he is one of three watchmakers in the town. I regularly bring him my watches whenever they need repairing for one reason or another: they might simply need a new battery or, in one particular case, because an important part needed to be replaced. The latter has had me calling in on Herr Grubmüller’s workshop at regular intervals for some time now. Indeed, my most expensive watch has been in his workshop for several years now as the part that needs replacing is no longer available. But evidently, there is still hope of it being sourced at some point. In any case I’m well acquainted with the shop, and I always get to hear the latest news: about a burglary and the exciting investigation that followed, or the time water flooded the shop. Whenever I call in to see him, Herr Grubmüller likes to show me the watch mechanism he made for his master craftsman’s diploma in the 1970s.

Our butcher, who runs a cinema

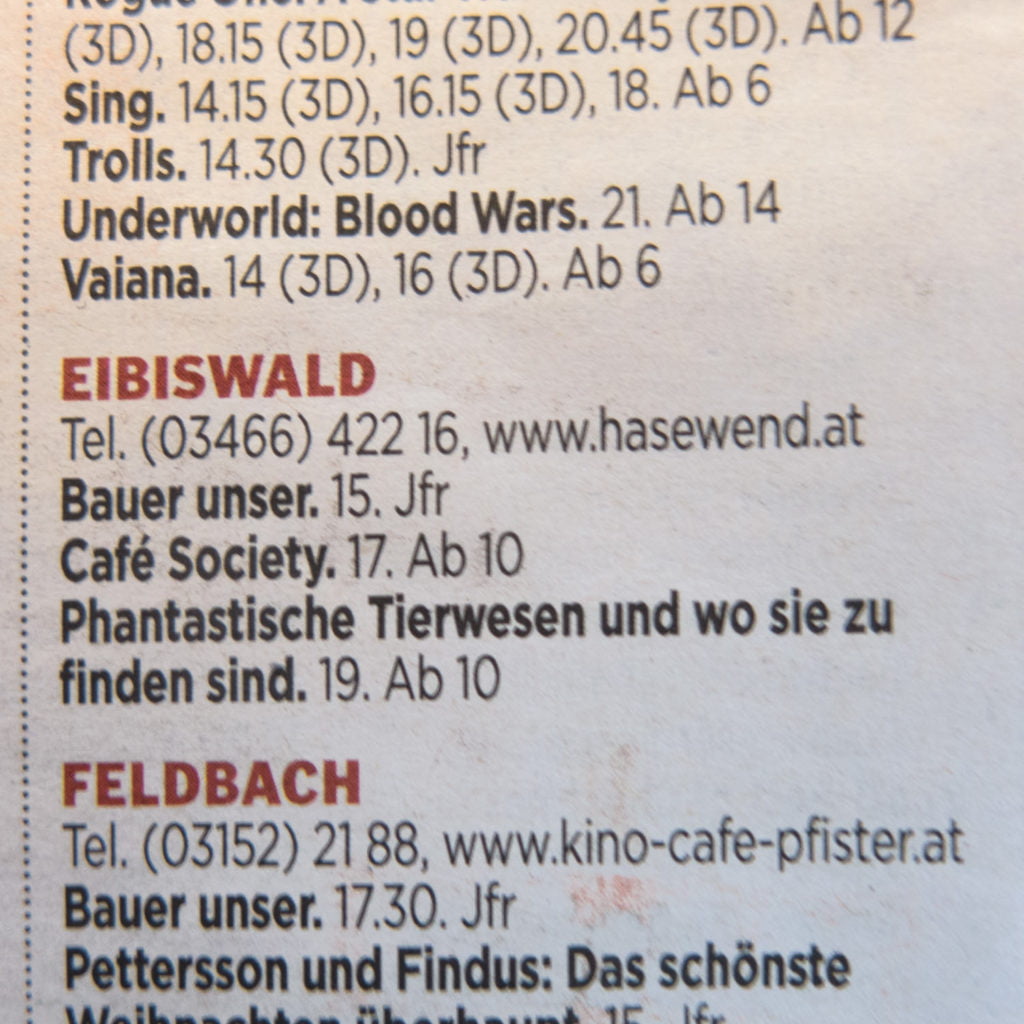

One of the oldest houses in Eibiswald has an interesting combination of businesses:

it’s here that the Hasewend family runs a restaurant called Hasewend’s Kirchenwirt, a butcher’s shop with adjoining delicatessen, and a cinema. We’ve often been invited to the restaurant for receptions after a funeral, and on such occasions the beautiful function rooms on the upper floor are just about spacious enough. In the butcher’s shop Herr Hasewend sells everything he is able to prepare as a master butcher, sourced from local farms: from fish and cheese to wine and medicinal and aromatic herbs. And then there’s the cinema. It has been running without interruption since 1913 in a room adjoining the restaurant; in the 1990s it was renovated and upgraded with state-of- the-art technology. The repertory programme screened by the Hasewend Family is comparable to that of the art-house cinemas you find in larger towns and cities. The topic of sustainable and sensible food production is often the focal point of discussion. The fact that these films enjoy a large and receptive audience should reassure those who believe that ‘the countryside’ has been lost once and for all as a place of critical thinking about the future we all share in common.

Manfred Willmann, born in Graz in 1952. Numerous exhibitions since 1972. From 1975 to 1996 head of the photo gallery in the Forum Stadtpark; Founder (1980) and until 2009 editor of the journal Camera Austria International. Lives in Graz.

Work and Recollection by Manfred Willmann focuses on everyday situations taken from the artist’s personal surroundings, exploring the need for manual skills in everyday working life and the way in which his protagonists are integrated into social realities. The photographs taken in the Austrian province of Styria consist of extended portraits that showcase the sphere of activity of these protagonists and its specifics in all its details and significance. They illustrate the history of traditional working methods which, increasingly, are giving way to digital and machine-controlled processes and losing their public profile as a result.

Willmann portrays the working and living environment of his tailor, his car mechanic, the watchmaker, and the simultaneous operator of a cinema, butcher’s shop and restaurant, as well as his grandfather with his passion for basket weaving. And while not all the protagonists enter the field of view directly, all the professions portrayed are linked to notions of work as evidence of craftsmanship that demands a particular dedication on the part of those involved. Willmann remembers a generation who engaged in a multitude of activities such as these, activities which very few people today still master. Willmann’s work is characterised by focusing on identity-defining details which, as a narrative strand, are in keeping with the principles of auteur photography.

Willmann’s car mechanic for instance is portrayed within the standard heteronormative context of his profession, complete with pin-up posters on the walls. But at the same time, the mechanic’s artistic aspirations are highlighted as he creates sculptures from bits of leftover metal, to be used as ashtrays. The meticulously precise work of Willmann’s tailor is documented by the countless darts and detailed seams sewn on a jacket, all of which are necessary to achieve an exact outline and fit. At the same time he also depicts the painstakingly tidy setting in which the tailor has gone about his work until very recently, a setting unchanged since 1958. The watchmaker, too, devotes himself with the utmost accuracy to the precision engineering of his timepieces.

The images of countless baskets woven by Willmann’s grandfather are contrasted with a photograph that shows a ‘historical’ picture of the artist in the form of a childhood photo. Next to this ‘picture within a picture’ is a head shaped out of plasticine, a likeness of Willmann’s grandfather, now deceased, that he made as a pupil, its image taking the place of the portrait of the protagonist in the other series.

The photographs document a time as a moment of recollection when work meant the ability to identify with a craft and industrial manufacturing processes were not yet the order of the day. Within this circle of acquaintances that Willmann portrays, he succeeds in retracing a lifestyle in which a notion of work passed down through the generations is expressed in both a rural and an urban setting.

Walter Seidl, born in Graz in 1973. He has curated numerous exhibition projects in Europe, the US and Japan, and contributed essays for artist’s monographs and international magazines, including Camera Austria, springerin and Život umjetnosti. He is a curator, author, and artist, and lives in Vienna.