Nora Schoeller

The Political Landscape

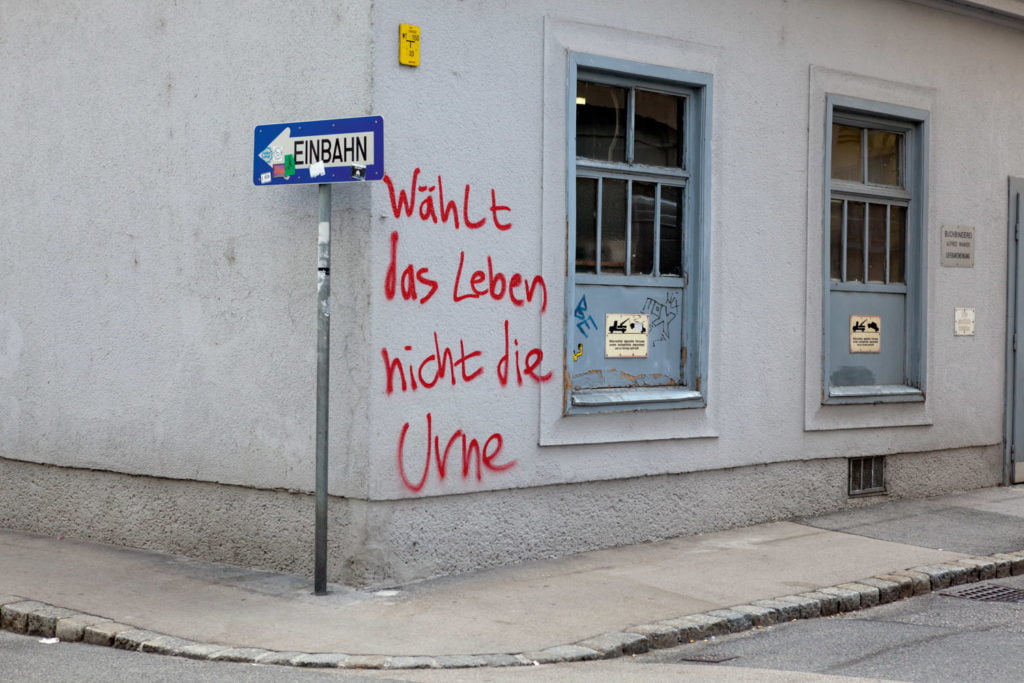

2016: Austria’s political landscape is in upheaval, and the atmosphere is tense. That’s reflected not just at the centres of political activity, but also increasingly at the margins. My photographs and the way in which they are put together seek to capture that mood. They are snapshots which may also hint at future developments. What significance will established parties have in the future? What role will civil society’s involvement come to play?

Nora Schoeller

Nora Schoeller lives and works in Vienna. Publications: Vienna’s Ringstrasse (2014), Ignaz Gridl. Eisenkonstruktionen (2011), 21 Reportagen. Betrifft Fotografie (2008), Entdecken und Besitzen (2005).

Concerns over one’s media image are now firmly anchored within the political environment. Rightly so, of course. Only totalitarian regimes have control over how photographs are disseminated, how they are channelled into a media network that seems almost infinite, and how they are commented. Even a country as innocuous as Austria now has the jitters: those who feel misunderstood and/or badly treated ‘by the media’ are not in short supply. Which is why you’re not allowed to photograph anything you want from the viewers’ gallery of the Austrian Parliament. Anyone caught peeking over an MP’s shoulder while they play solitaire or shop online on their laptops during parliamentary sessions will be ejected – and rightly so, of course. With the standing of parliamentarians now at an all-time low among the general public, there’s no need to fan the flames even more…

So we need to make it clear that, at all the gatherings she documented, Nora Schoeller had the consent of those in charge when taking her photographs. They were the ones who specified where and when she could be present, even in those instances where the gatherings were scheduled in public spaces. After all, here, in these manageable spaces, everything is under control. The speaker addresses his or her audience, the anchor- person talks into the microphone, a round table debates late into the night, the radiant winner makes his or her appearance, and the election supervisor looks after the ballot box: ‘A very warm welcome…’ The locations change, and the succinct captions tell us we were right about our prejudices. In Parliament the traditional main parties convene in strict tiers of seats; on Vienna’s Yppenmarkt the ‘Aufbruch’ movement debates; in Lower Austria they still wear traditional costume; and the Social Democrats’ district branch is furnished with red upholstered furniture. However there is no telling visually what was under discussion in each case.

Can political beliefs only manifest themselves in images when people take to the streets and, as a result, lose control over their photographic likeness? It is certainly no coincidence that Schoeller chose the May 1 smoke throwers to kick off her series of images. The ever-present slogans at demonstrations – whether on T-shirts, banners, leaflets or giant wall texts – shout out their messages. Unmistakably so, the enthusiasts are probably thinking, yet the unbiased viewer (if there is such a thing) of these images may well wonder what Nazis flambieren [flambé the Nazis] is supposed to mean, or why people usually hold up the red-white-red ribbon with the blue inscription Aus Liebe zur Heimat [Out of love for the homeland] in front of their faces.

But even in a controlled environment, Schoeller has some enlightening things to offer those of us who choose to look closely: sometimes deliberately, sometimes randomly, as she says. She succeeds in making assembly rooms talk. Indeed, not everything appears to have been consciously determined by those convening there. Bruno Kreisky’s portrait or the crucifix as ever-present über-figures in the background seem premeditat- ed – but what’s that green armchair-back doing in the red district office? And are we to deduce from the exclusively young and female staff in the conservative parliamentary group who the real decision-makers in the party actually are? Hey, look what he’s doing! as a small poster behind the apparent chairpersons of a gathering of participants who appear equal only at first glance must serve as a call for us to take a close look and interpret with irony what is being presented to us in images: it is not possible to capture in a photograph, with all the implications, the commotion over the fact that, in the political environment documented by Schoeller in Austria in 2016, a presidential election had to be invalidated for the first time ever; rather, we need to bear it in mind continually as a backdrop to all the photographs.

Monika Faber, born in Vienna in 1954, studied art history and classical archeology in Vienna. From 1979 to 1999 she was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation Vienna. Thereafter she joined the Albertina (Vienna) as chief curator of the photography collection. Since 2011, she is head of Photoinstitut Bonartes in Vienna.