Seiichi Furuya

Asylum and flight: The example of Spielfeld

In September 2015 the number of refugees seeking to gain entry to Austria at the Spielfeld border crossing increased dramatically. Hungary had closed its border to Serbia, and so the flow of refugees made its way to Austria via Slovenia. Every week thousands of refugees gathered at the Spielfeld border crossing (by the end of 2015 there were around 190,000 people there).

At the end of 2015 the Republic of Austria decided to implement what it referred to as ‘border management’ at the border crossing itself. It consisted of a fence some four kilometres in length erected around the border crossing. In March 2016 the so-called Balkan route for refugees heading north was shut down, once and for all. At that same time the agreement on refugees between the EU and Turkey came into force. As a result of these decisions the influx of people fleeing to Austria (and, for some, onward to Germany) via Spielfeld was halted almost entirely. At present no-one knows if and when the border fence around Spielfeld (a fence that was not even deemed necessary during the Cold War) will ever be dismantled again.

Asylum applications in Austria

2016 about 42.000

2015 about 89.000

2014 about 28.000

2013 about 17.000

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior

Numbers on Migrants & Refugees:

2016

387.487 arrivals into the EU

363.348 by sea

24.139 by land

5.079 dead / missing – Mediterranean

2015

1.046.599 arrivals into the EU

1.011.712 by sea

34.887 by land

3.735 dead / missing – Mediterranean

Source: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Austria

Seiichi Furuya, born in 1950 in Izu, Japan, studied at the Tokyo Polytechnic University. He lives and works in Graz.

www.furuya.at

‘Something is contingent insofar as it is neither necessary nor impossible; it is just what it is (or was or will be), though it could also be otherwise. The concept thus describes something given (something experienced, expected, remembered, fantasized) in the light of its possibly being otherwise; it describes objects within the horizon of possible variations.’ [ref]Niklas Luhmann, Social Systems, translated by John Bednarz, Jr., with Dirk Baecker, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1995, p. 106.[/ref]It’s this notion of contingency as described by sociologist and social theorist Niklas Luhmann in Social Systems that first springs to my mind when I consider Seiichi Furuya’s new work on his most enduring theme: the theme of the (Austrian) state border.

Furuya has continually explored the theme of borders and boundaries since the early 1980s. And since then he has also continually revised and reviewed not only his first photographs but also his subsequent ones, updating them (also pictorially) and adding new written commentaries – in keeping with the changes in situation brought on by processes of historical and political change.

Only two years ago, in 2014, Seiichi Furuya decided to bring out his (earliest) work on the theme of state borders in book form[ref]See Seiichi Furuya, Staatsgrenze, 1981–1983, Leipzig: Spector Books 2014.[/ref] , but not without addressing once again the open ends that accompanied the project from the outset. However, when the book was published two years ago, no-one could have foreseen that Europe’s post-war order would prove so brittle and that the European unification process made possible with the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 would now be called into question to such an extent in the light of the current political situation.

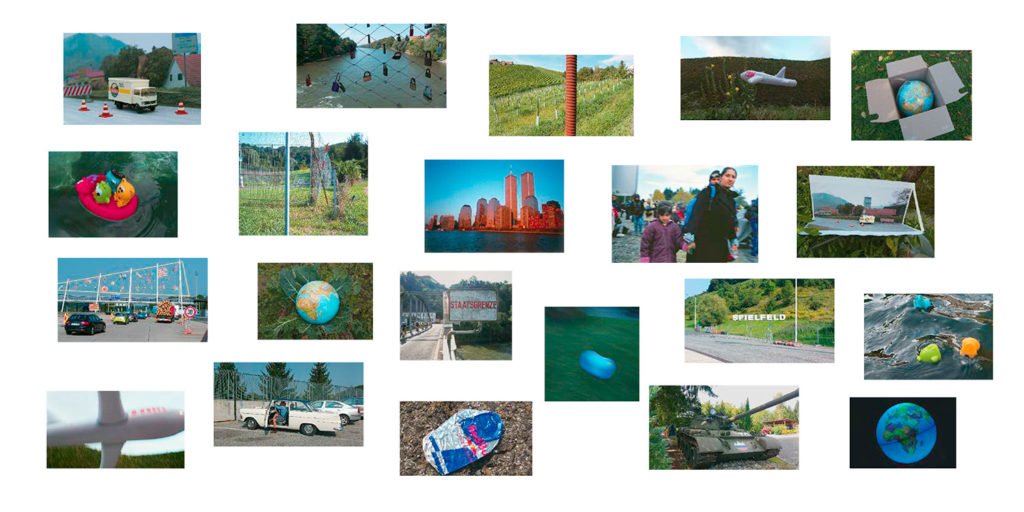

Perhaps that is the reason why, in this new work, Furuya abandons a conceptually sober approach in favour of a kaleidoscope-like work method. On the one hand his pictures feature photographs of the Austrian-Slovenian border post at Spielfeld and the border fence that was erected there in 2015: a fence not even deemed necessary during the Cold War in order to isolate Austria from what was then Yugoslavia. That fence therefore represents a new phenomenon for this strip of land. On the other, Furuya also depicts civil-war refugees on the Austrian side of the border, i.e. people who have managed to enter Austria via the Balkan route and the border town of Spielfeld (a border crossing which, given the new supervisory bodies is now hardly ever used). These documentary pictures are complemented by photographs of toys laid out by the artist in his own garden: a miniature lorry, an inflatable airplane, plastic figures in a boat on and in the water. The scenes recreated here are reminiscent of current events and their images in the media that focus on the personal destinies of those entirely un-free people whose flight ended with their unacceptable death – they were and still are the trigger of current political intrigues. Here, Furuya is deliberately not working with (say, any found) documentary material, preferring instead to recreate scenes.

I interpret this as much as a reference to the personal revulsion felt by the foreigner Seiichi Furuya in Austria as his work with those (at times repugnant) slogans that currently dominate the abysmal political discussion that surrounds refugees and the way in which they are portrayed in the media. These slogans are included with the photographs. And so the [German] Wikipedia entry on the keyword Spielfeld quoted here not only becomes the bitter core of the work, but also a biting commentary on the questionable political decision-making processes and populist legitimisation strategies with regard to the so-called refugee issue. They have contrived not only to make the unthinkable possible, i.e. once again to put up a border fence to largely suppress the influx of (a ridiculous number) of people from war-torn zones and crisis areas, but also to fundamentally put at risk the European unification process.

These more recent anti-European aspirations to hegemony have now become tangible with the Brexit vote and with Trump’s election; they are also threatening to consolidate further, both in Austria and throughout Europe in the light of right-wing populist and nationalist trends. They demonstrate that the status of the state border remains not just fragile and uncertain, but also possibly the concrete expression of a backward-looking Europe.

The issue of state borders is not coming to an end; rather, it remains unpredictable, and contingent. Seiichi Furuya’s new (commissioned) work demonstrates this.

And it is interesting to note that photography as Furuya uses it here is less about documenting than about serving as a means of formulating questions to the future. However, what the answers will be has little to do with our expectations; indeed, by now at the latest, we already know that things can always turn out completely differently.

Maren Lübbke-Tidow, born 1968 in Düsseldorf, lives as a freelance author and curator in Berlin.