Paul Albert Leitner

Tyrol: Reality Check (2016)

Paul Albert Leitner, born in 1957 in Jenbach, Tyrol, has been working as a freelance artist since 1986. He lives and works in Vienna.

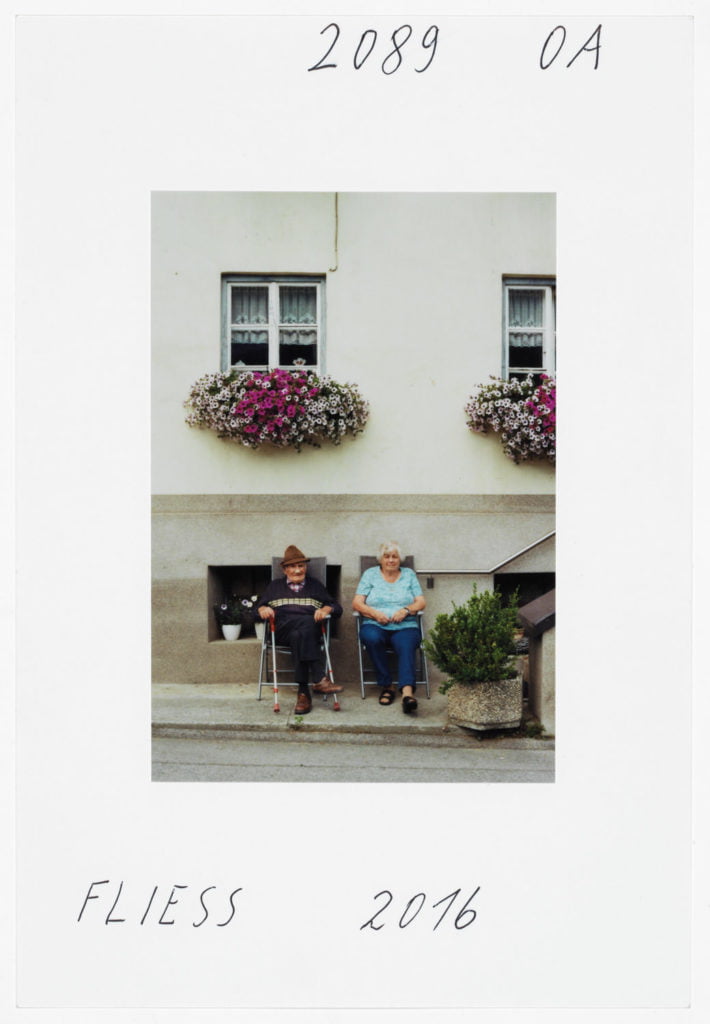

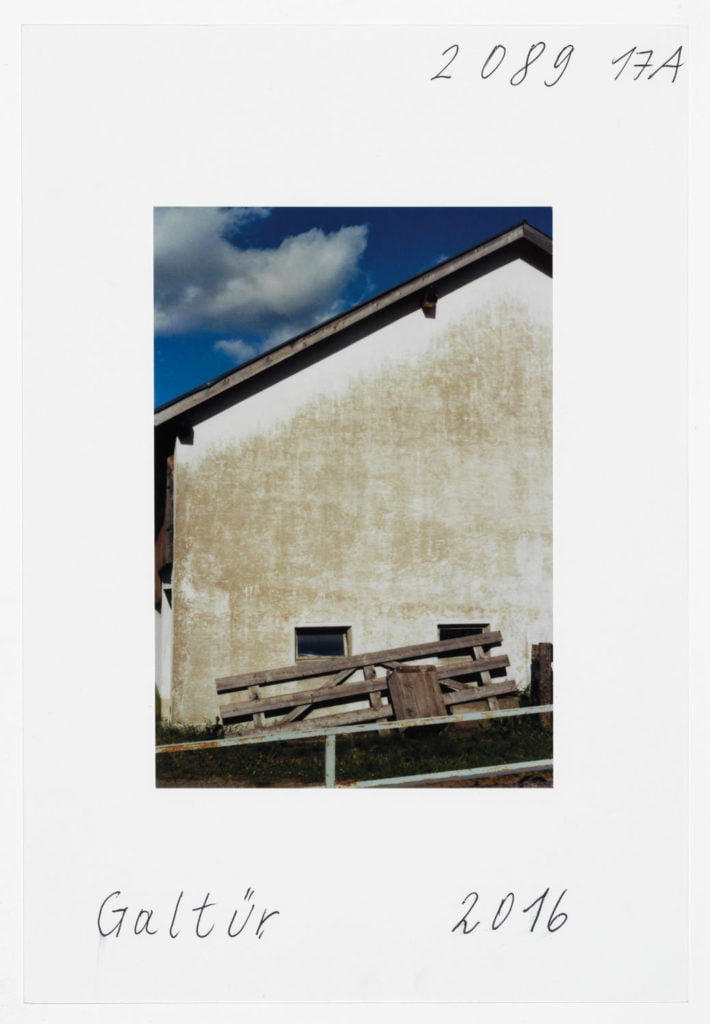

Baudrillard sees the miracle of the photograph radically in the fact that it shows the world to be non-objective[ref]‘The miracle of the photograph, of that allegedly objective image, is that through it the world shows itself to be radically non-objective.’ Jean Baudrillard, Impossible Exchange, London: Verso 2001, p. 139. [/ref]– an assumption that essentially characterises Paul Albert Leitner’s approach to photography. His world views are only apparently realistic, or documentary in nature; his gaze goes deeper; it gets to the bottom of things; it knows no contradiction between analytical and poetic, real and surreal; it’s on the trail of what lies behind the visible; it’s ironic, melancholy, joyful and tragic, narrative and laconic, witty and sad, surprising and at times banal, just like life itself.

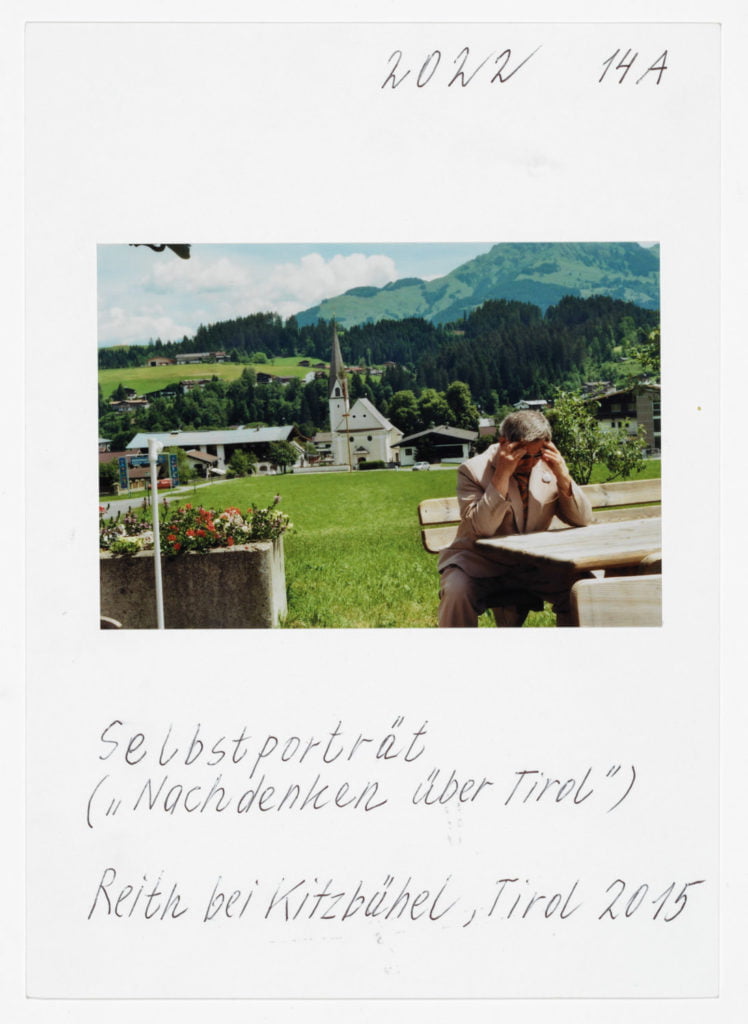

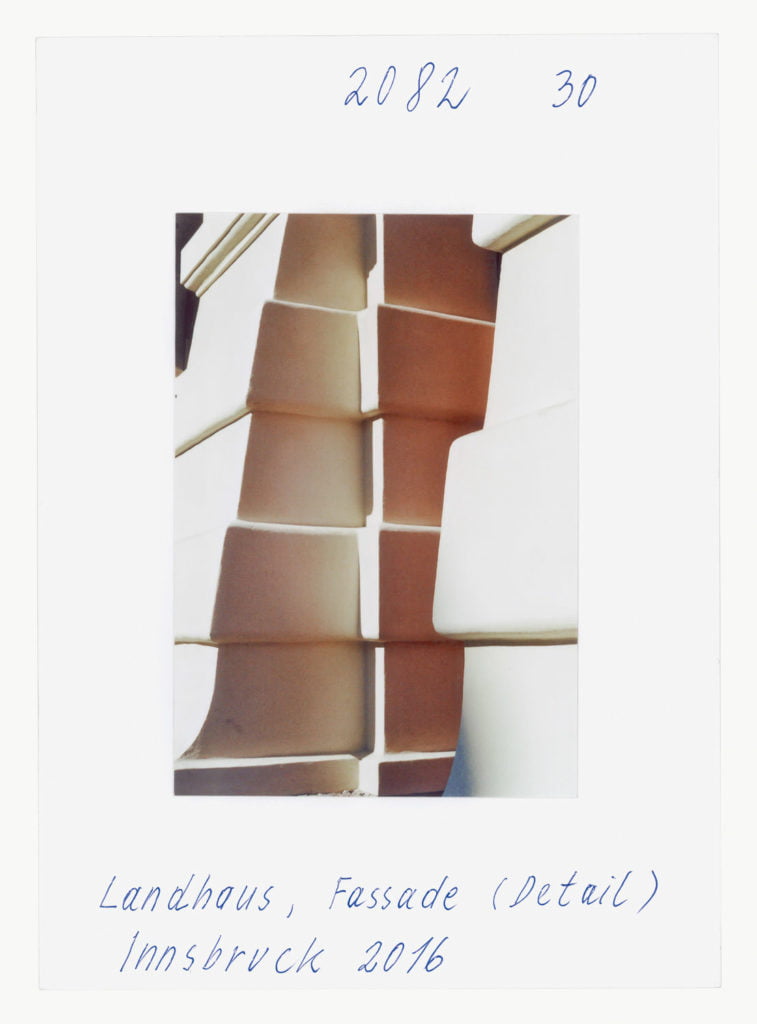

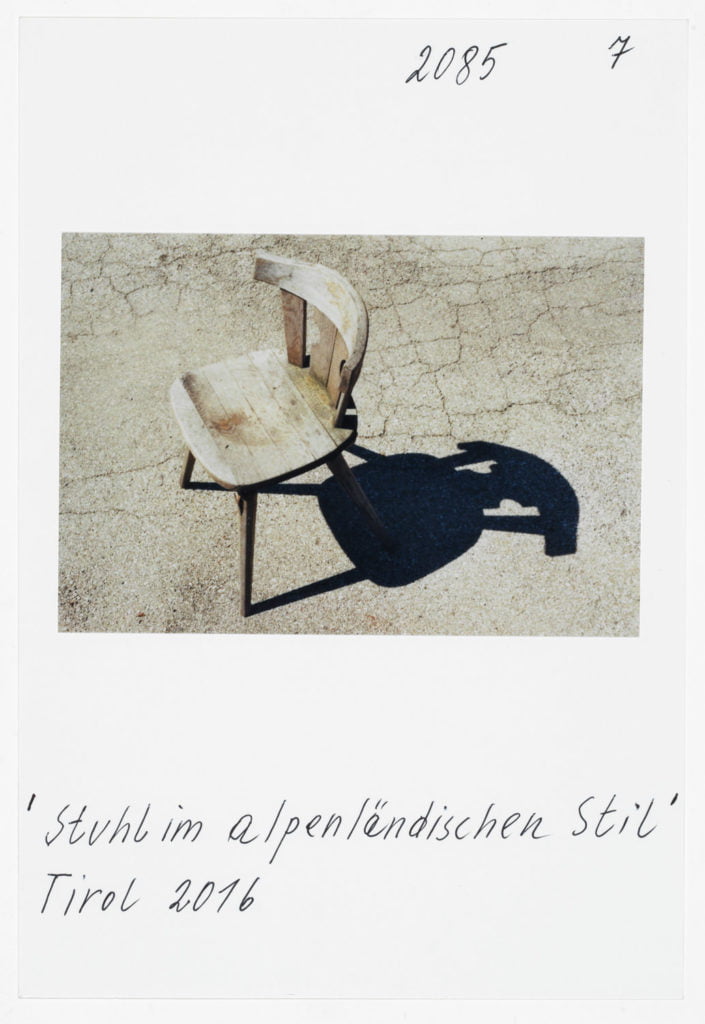

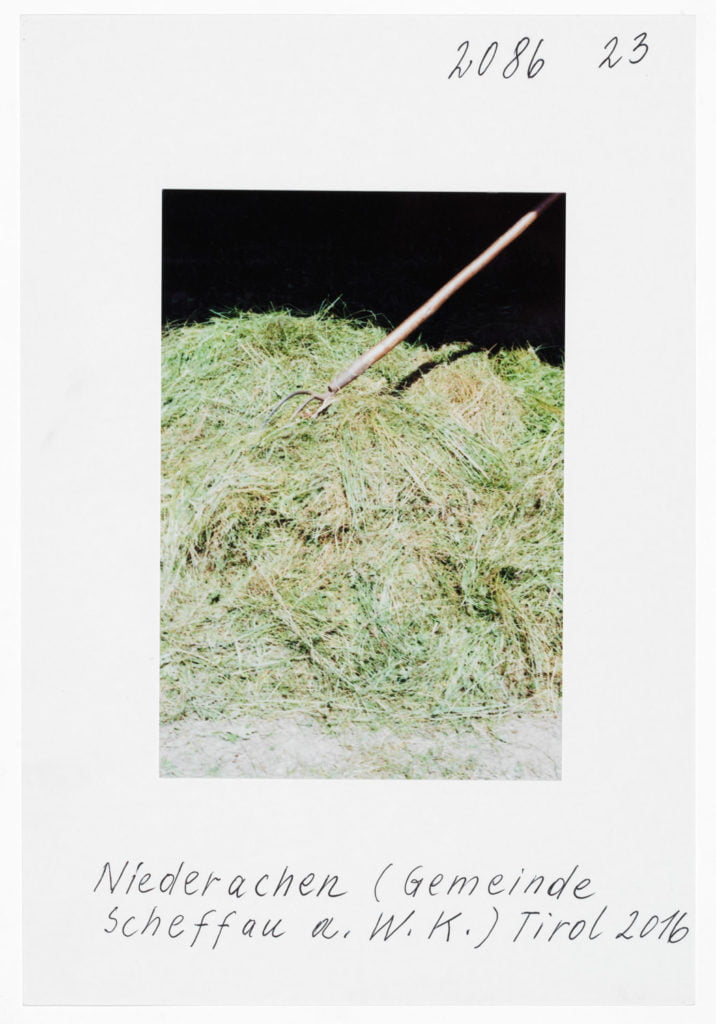

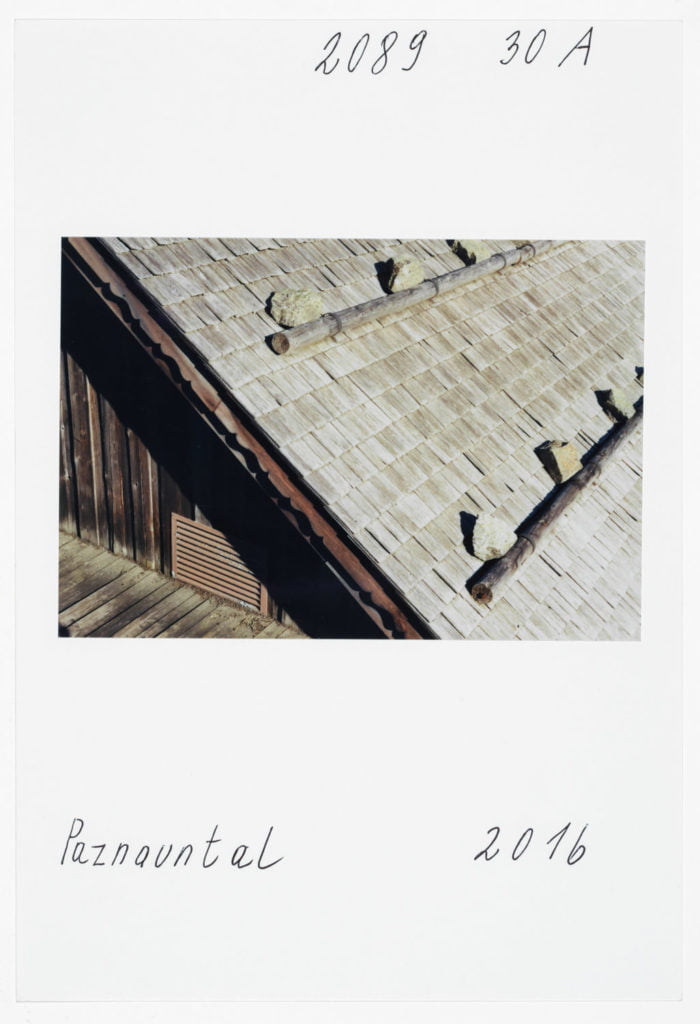

And so there is no contradiction, for me, between collages in which he accumulates found objects into a new reality, his own reality, and the images of individual objects, items of everyday life which, as in his photographs of Tyrol, transform a clunky wooden chair into an icon of the Alpine. Because ultimately Leitner’s images are formed in the mind before they become reality. And so when Leitner embarks on a photographic journey to Tyrol, it seems he is ‘driving his homeland home’ as it were.

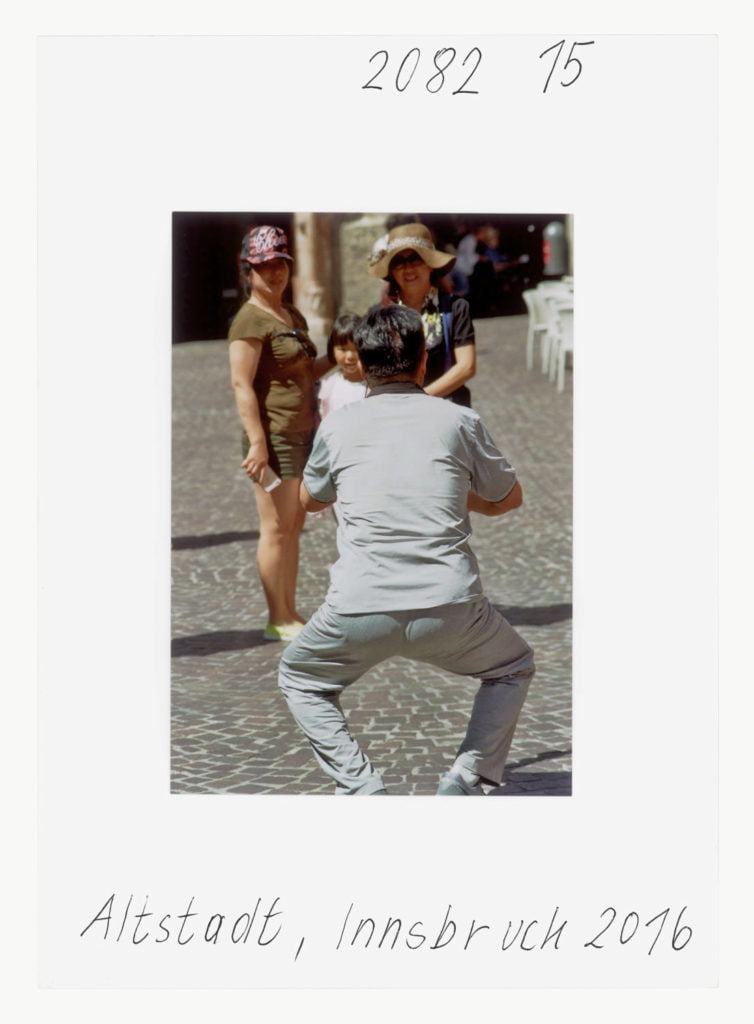

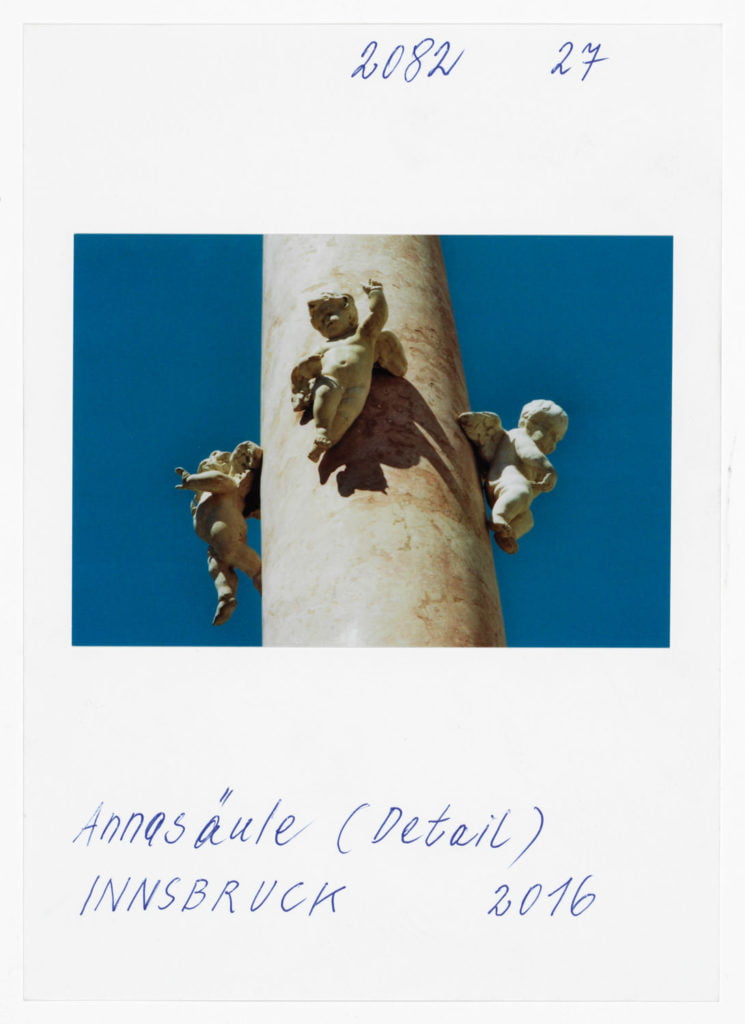

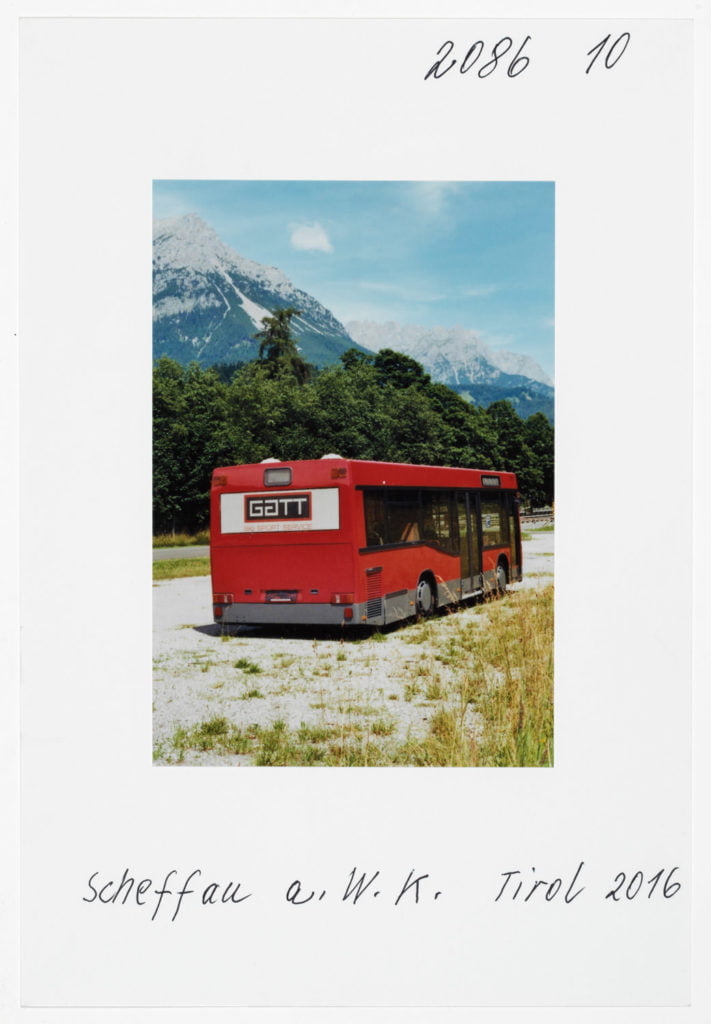

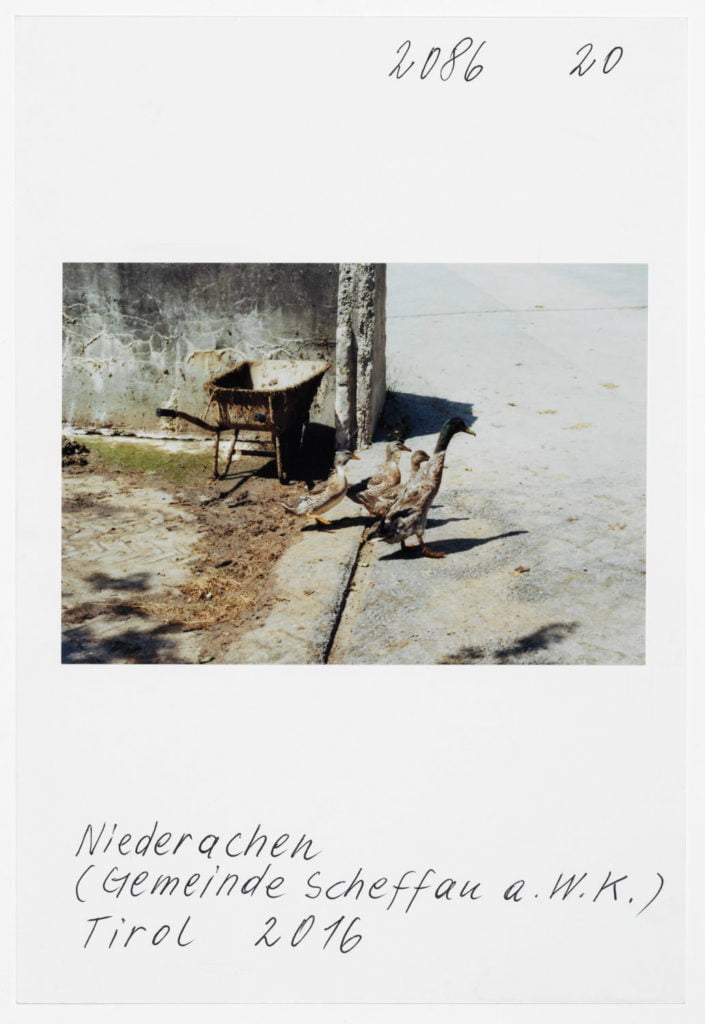

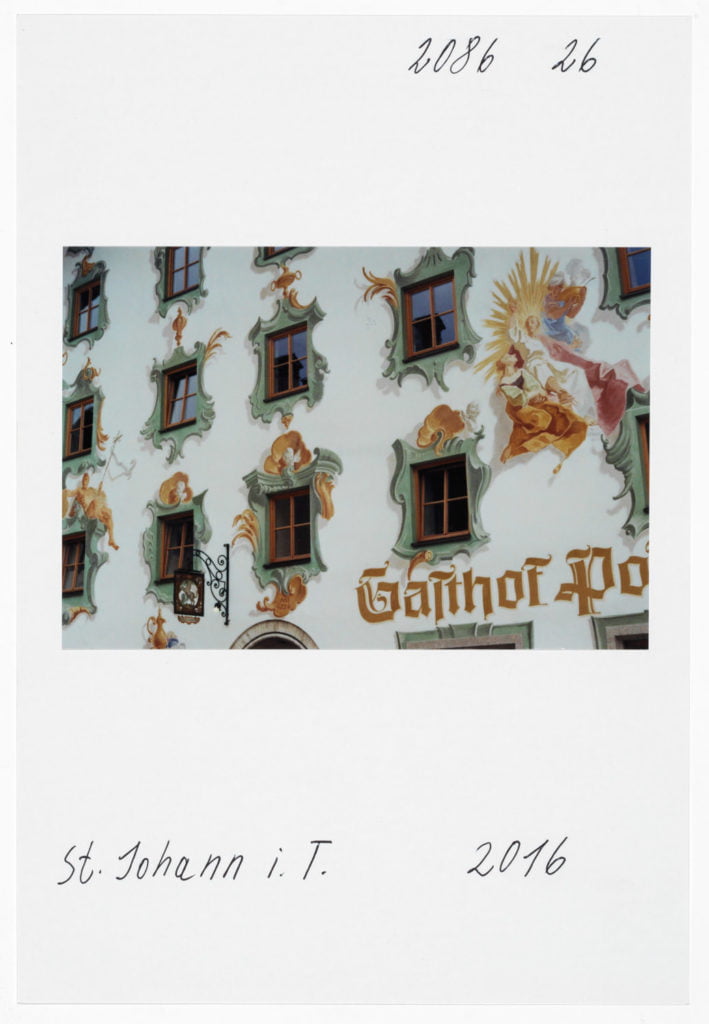

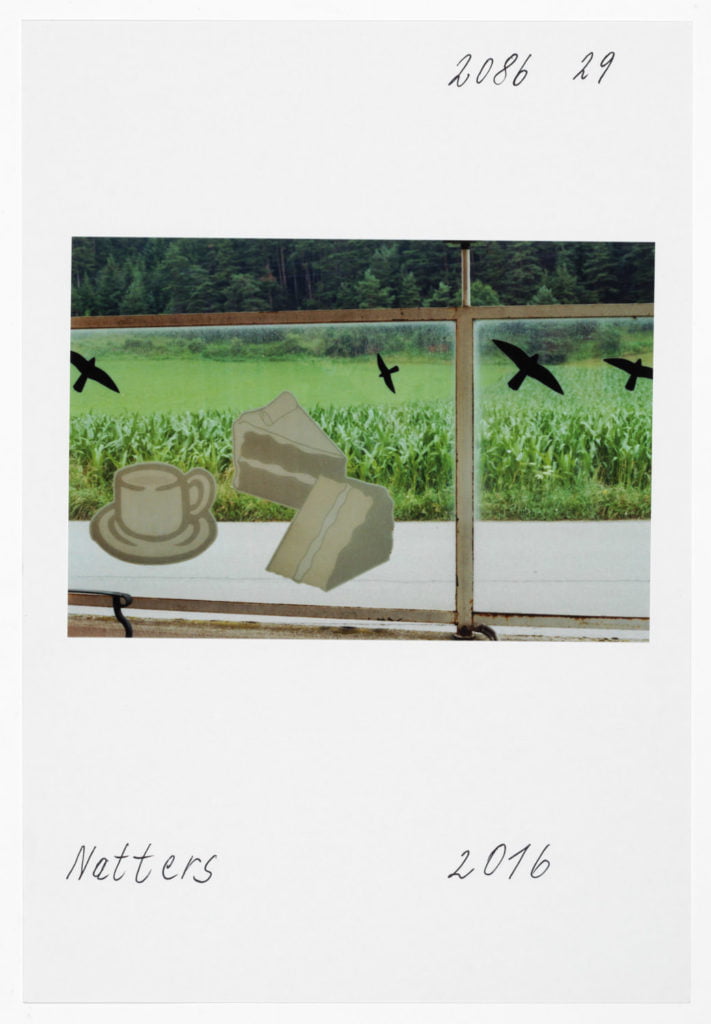

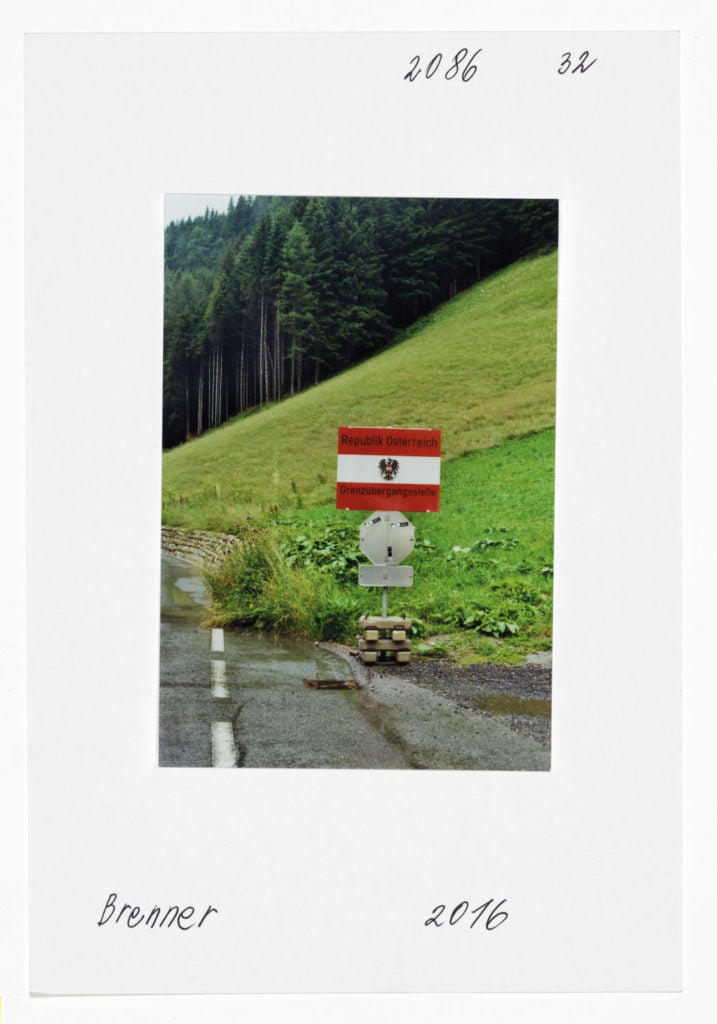

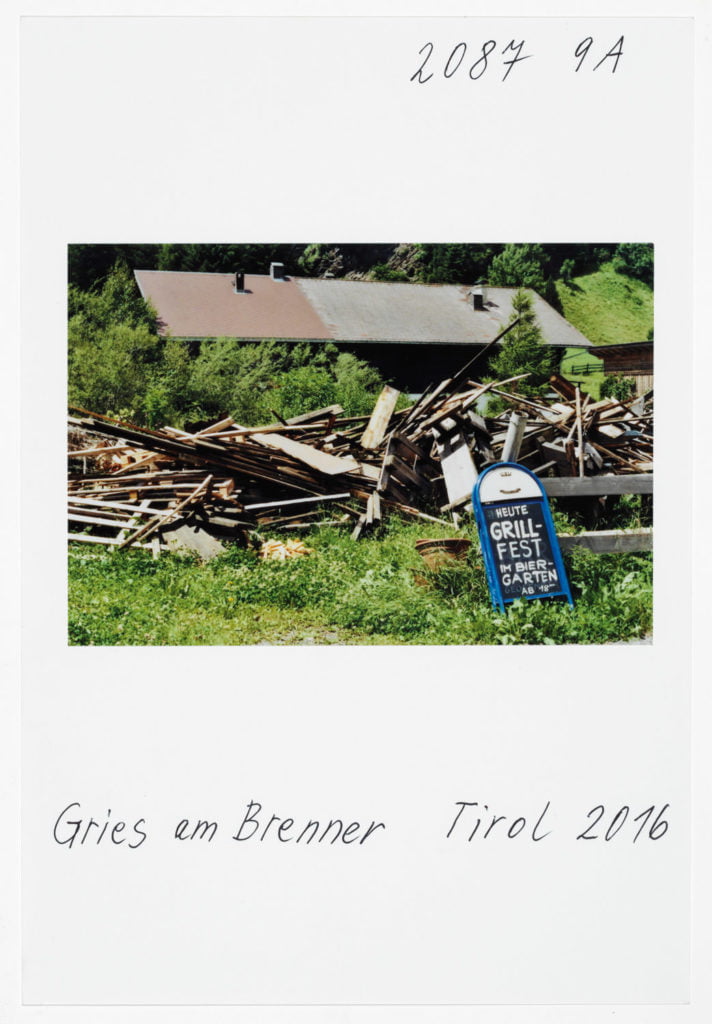

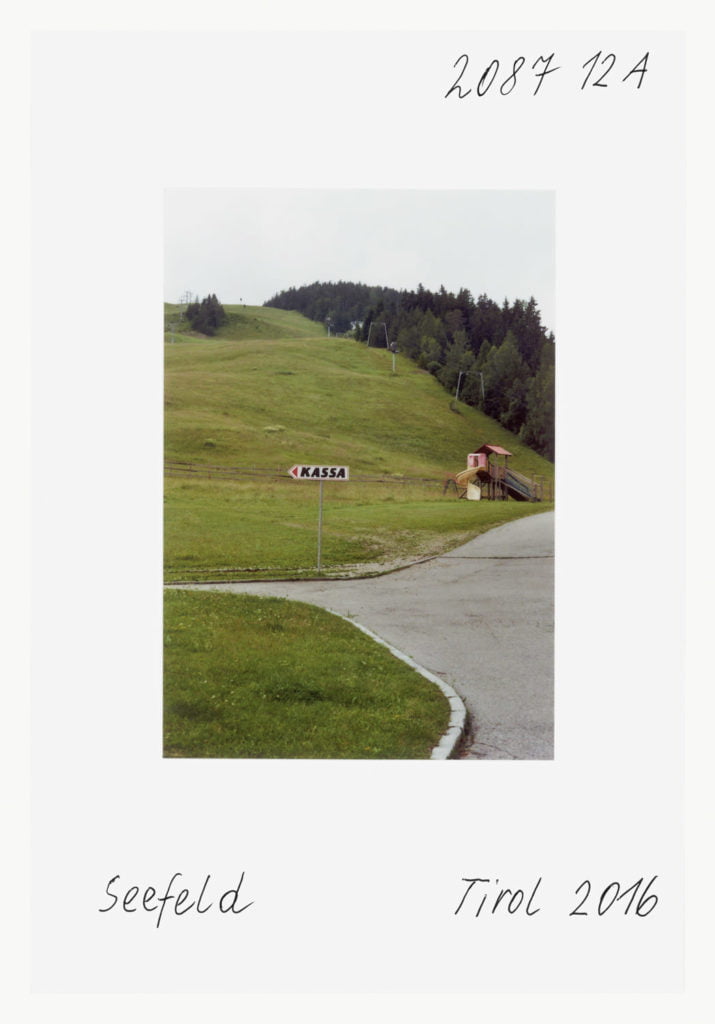

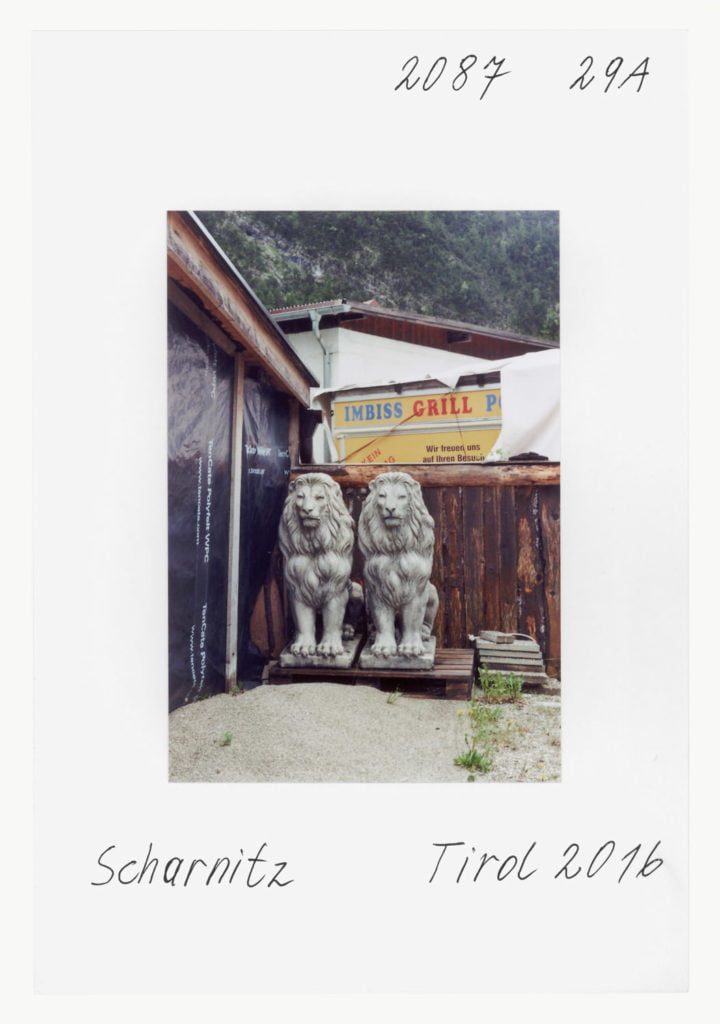

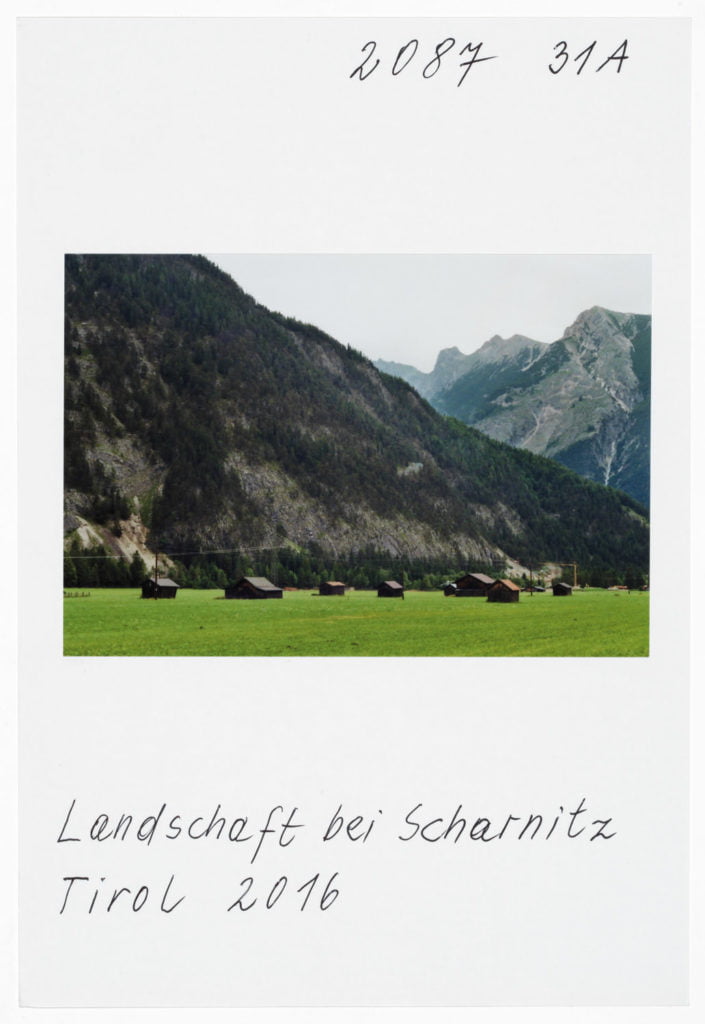

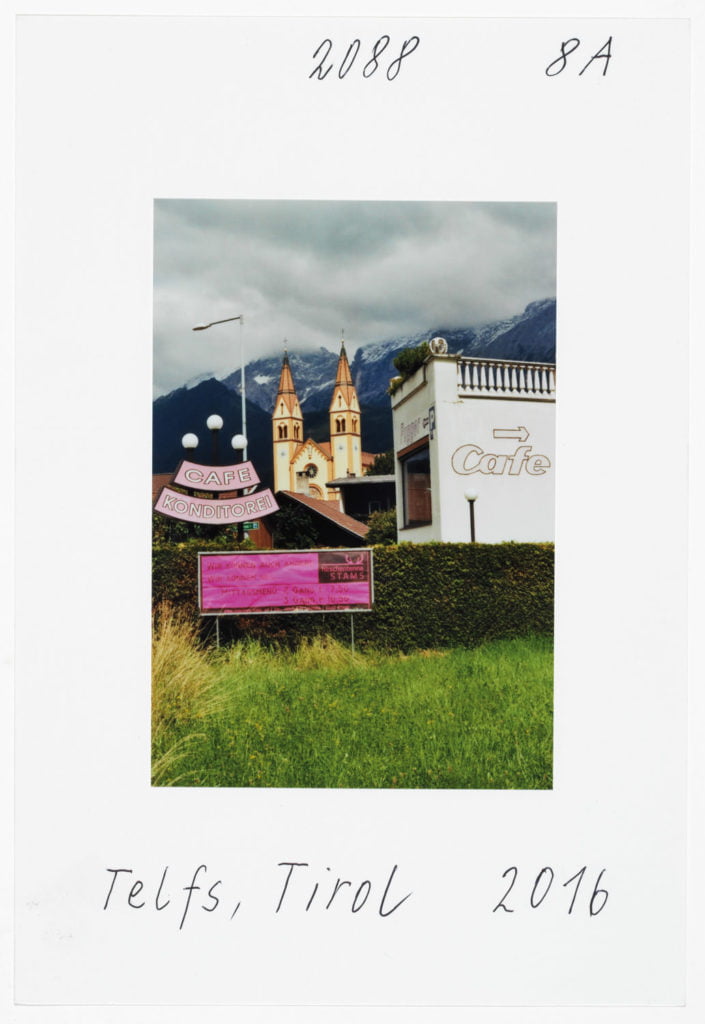

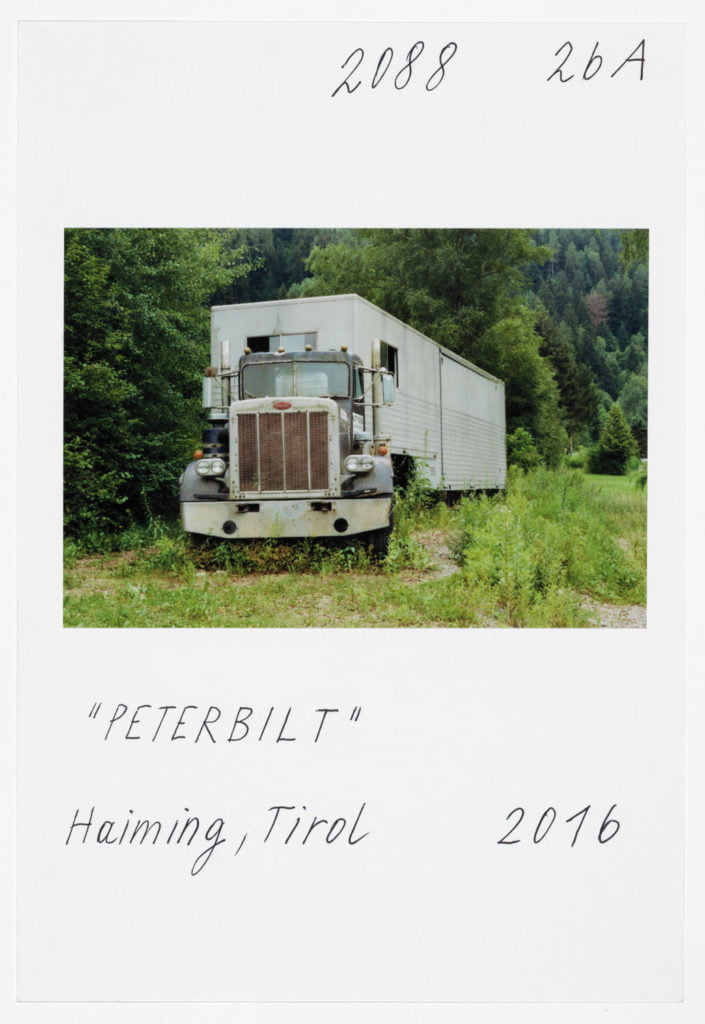

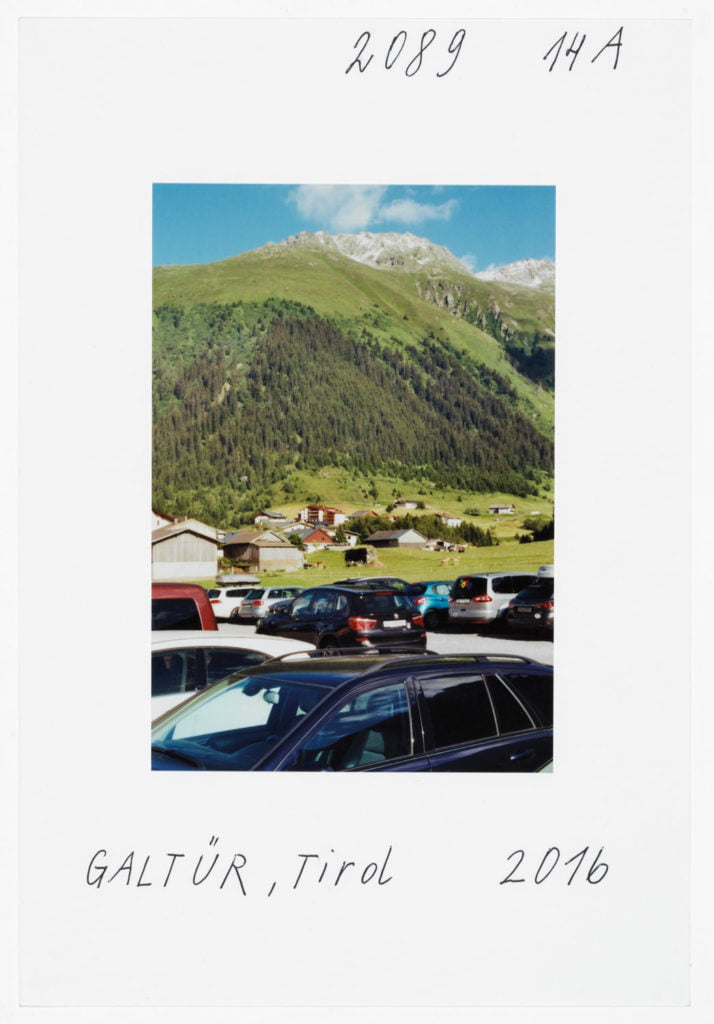

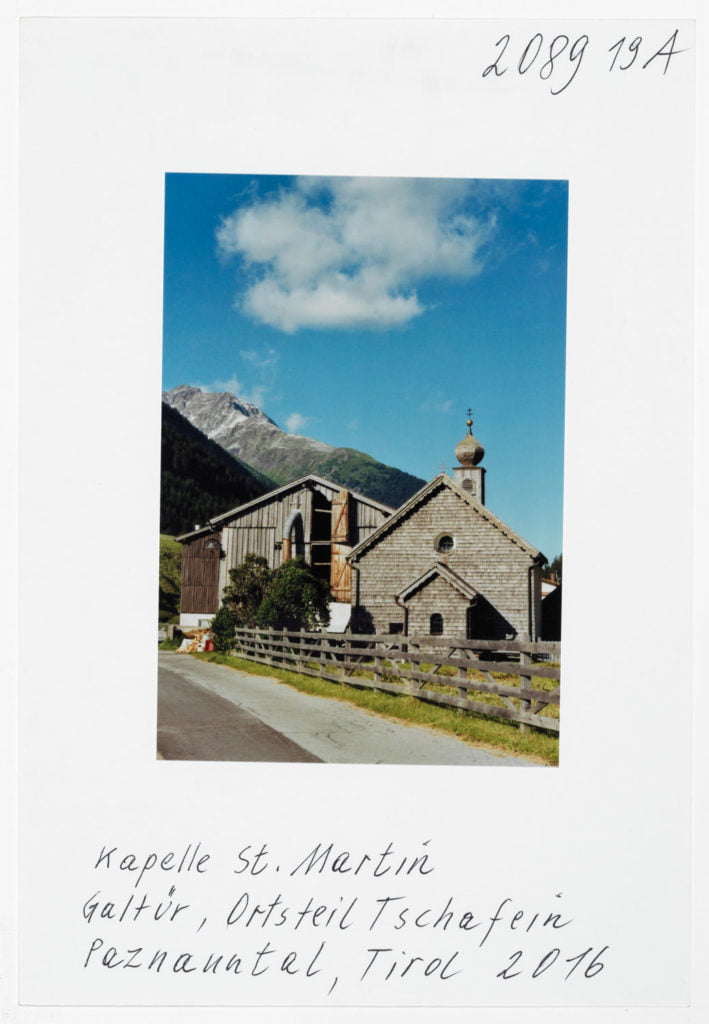

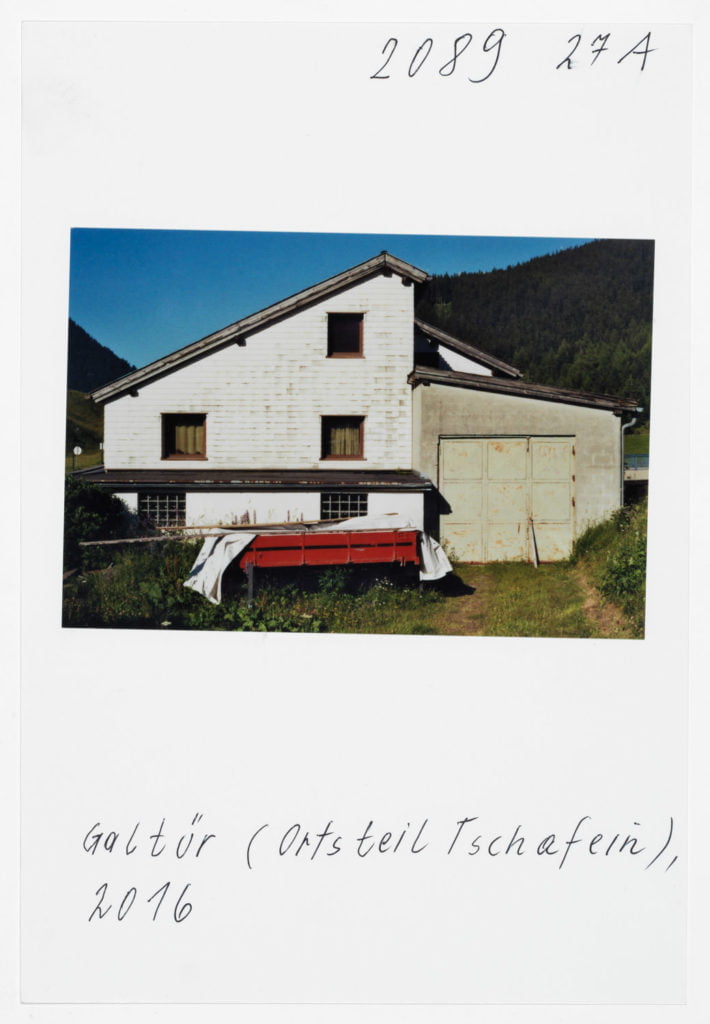

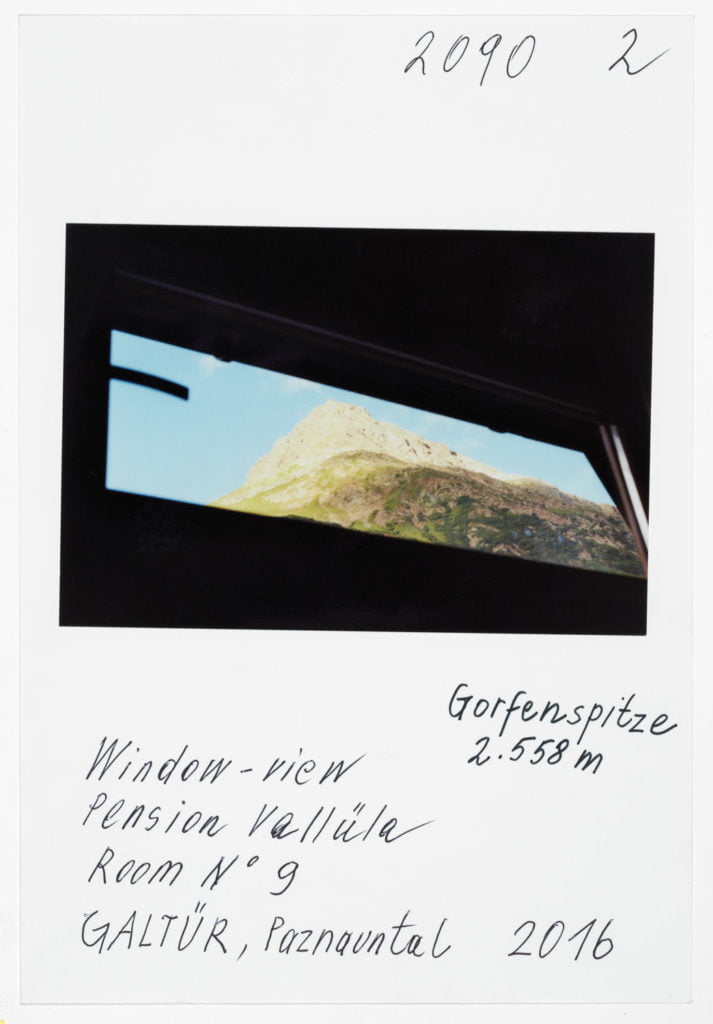

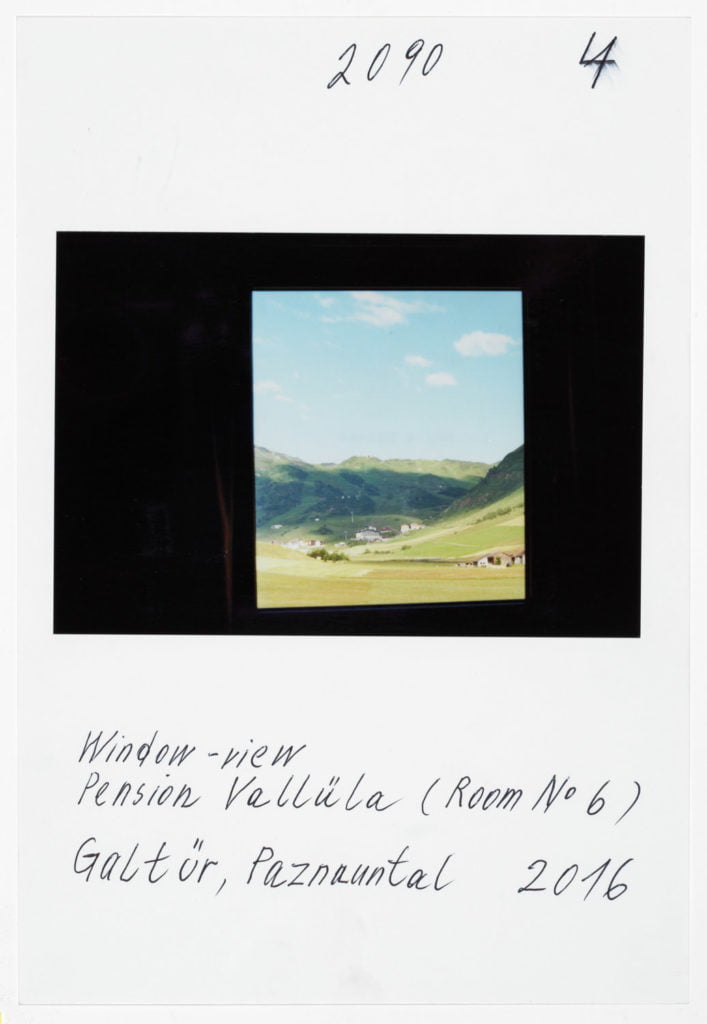

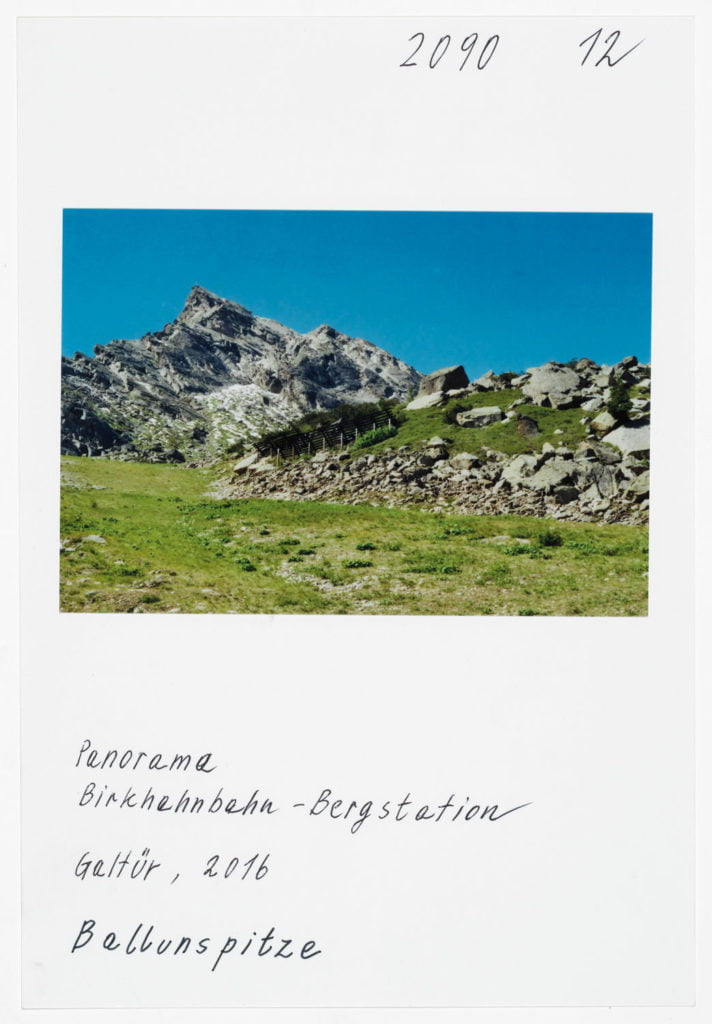

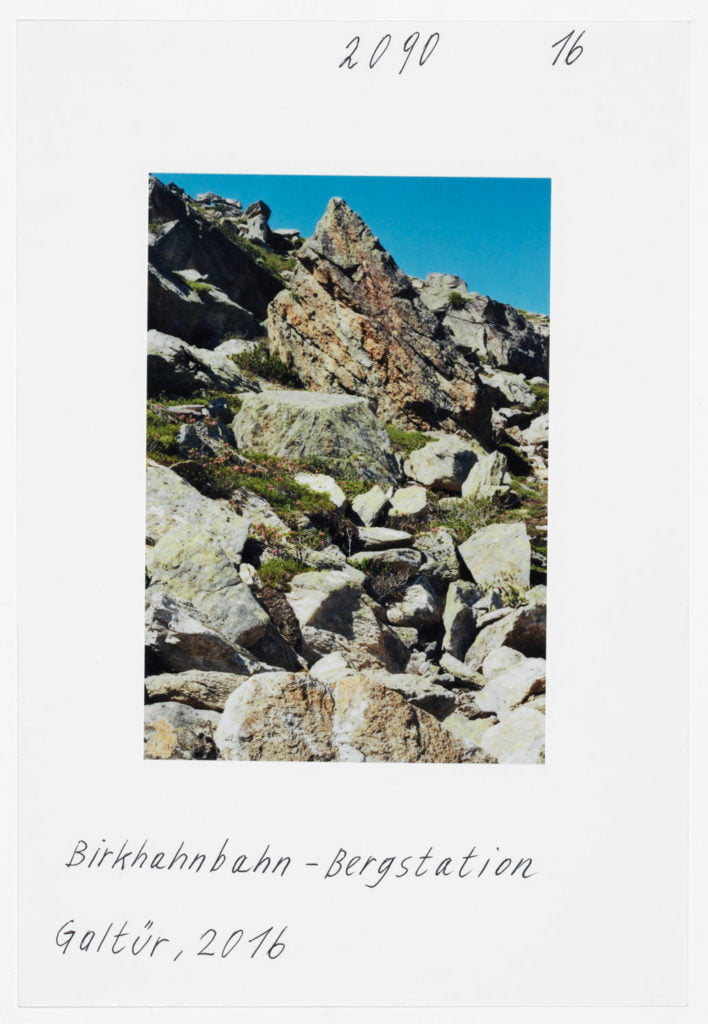

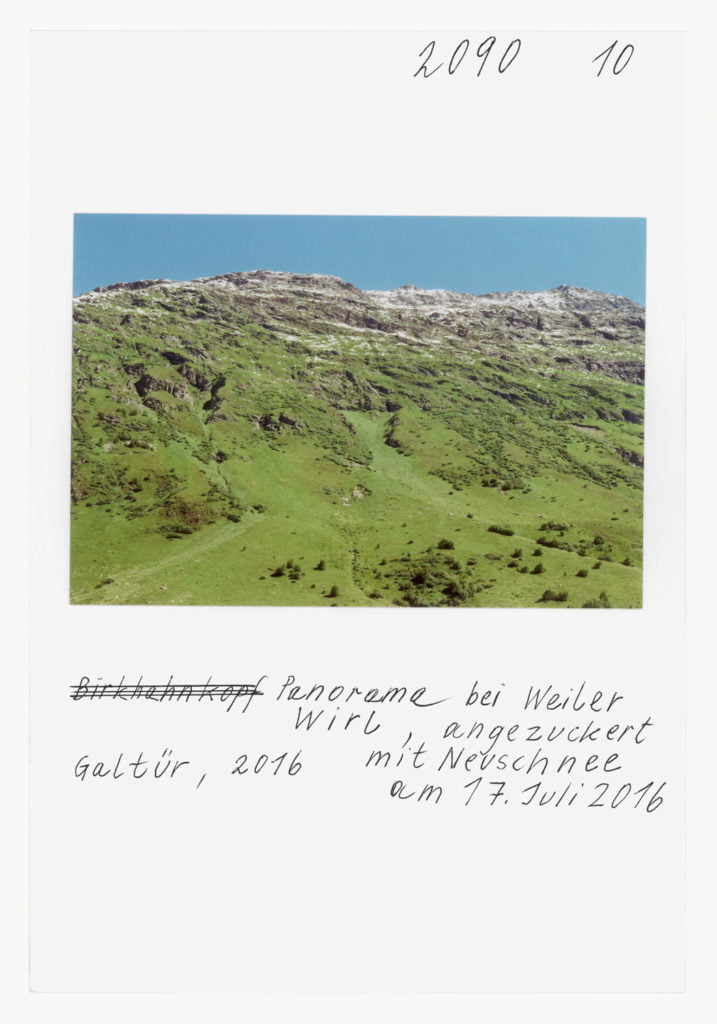

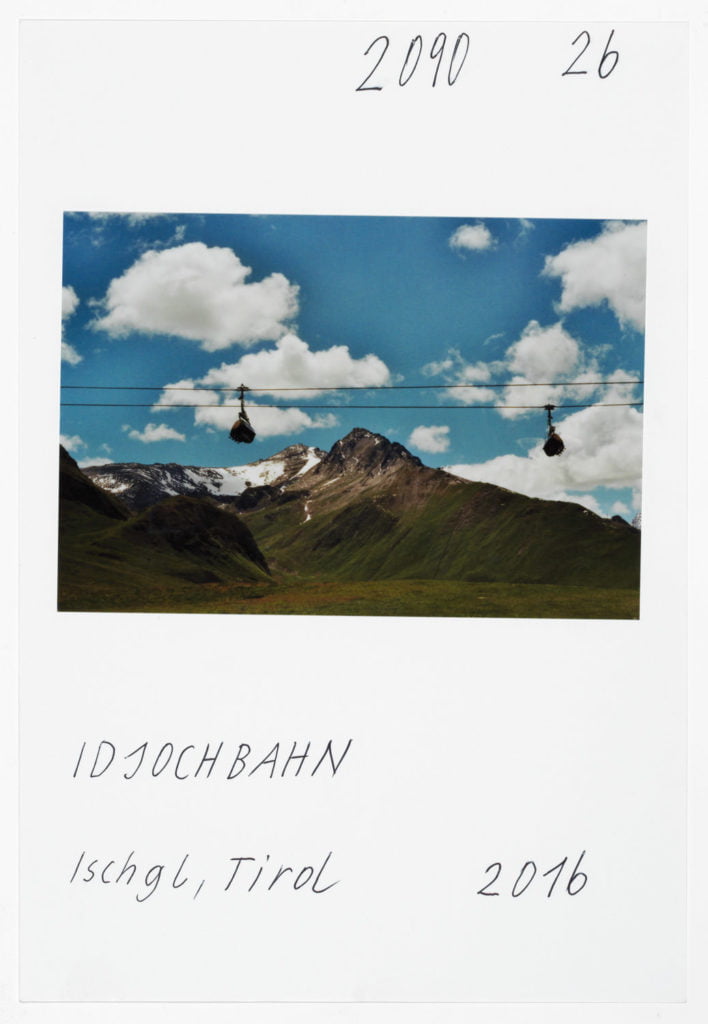

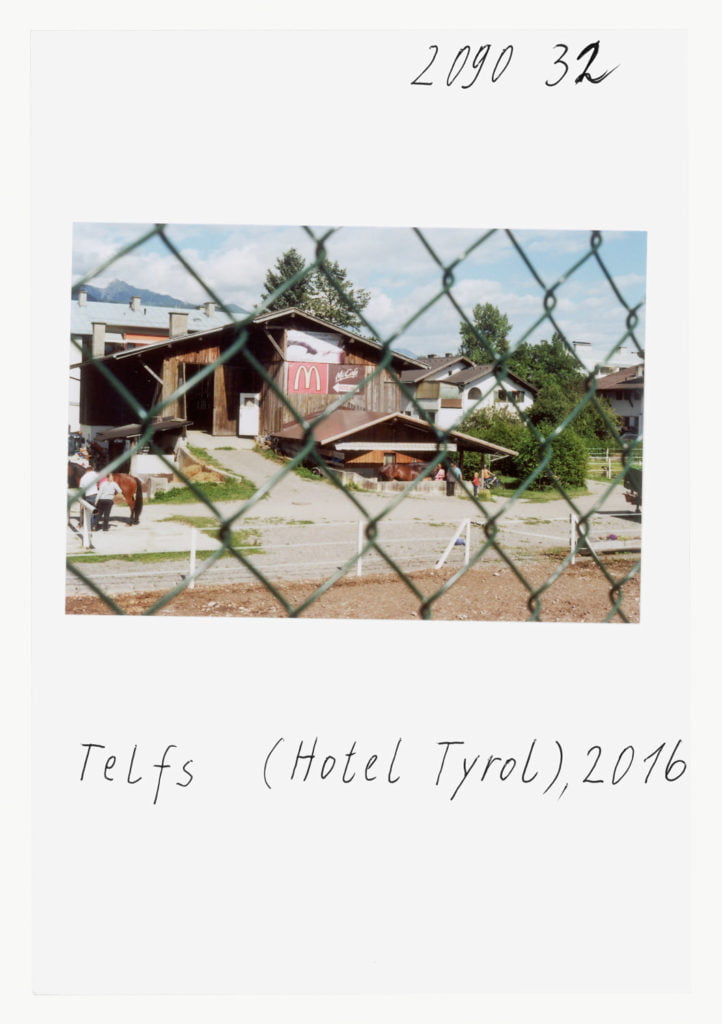

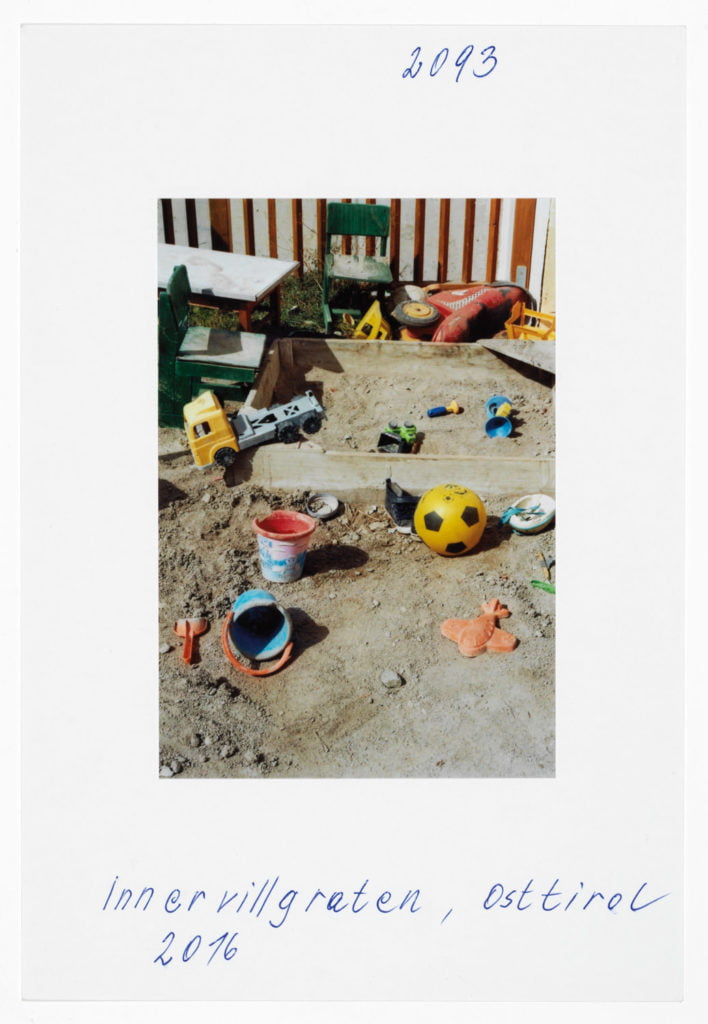

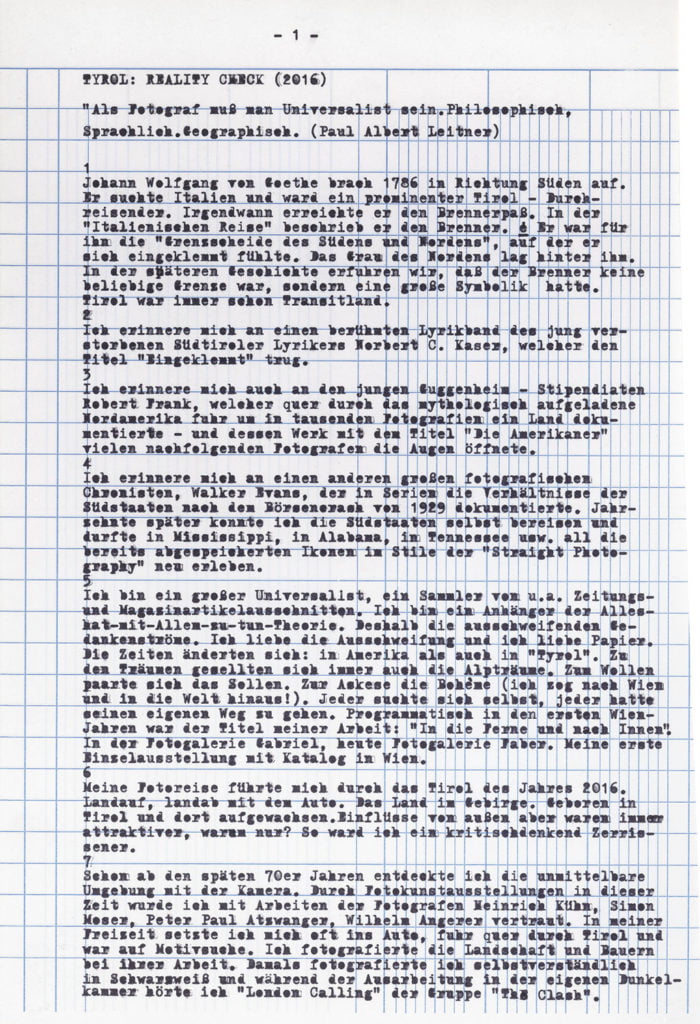

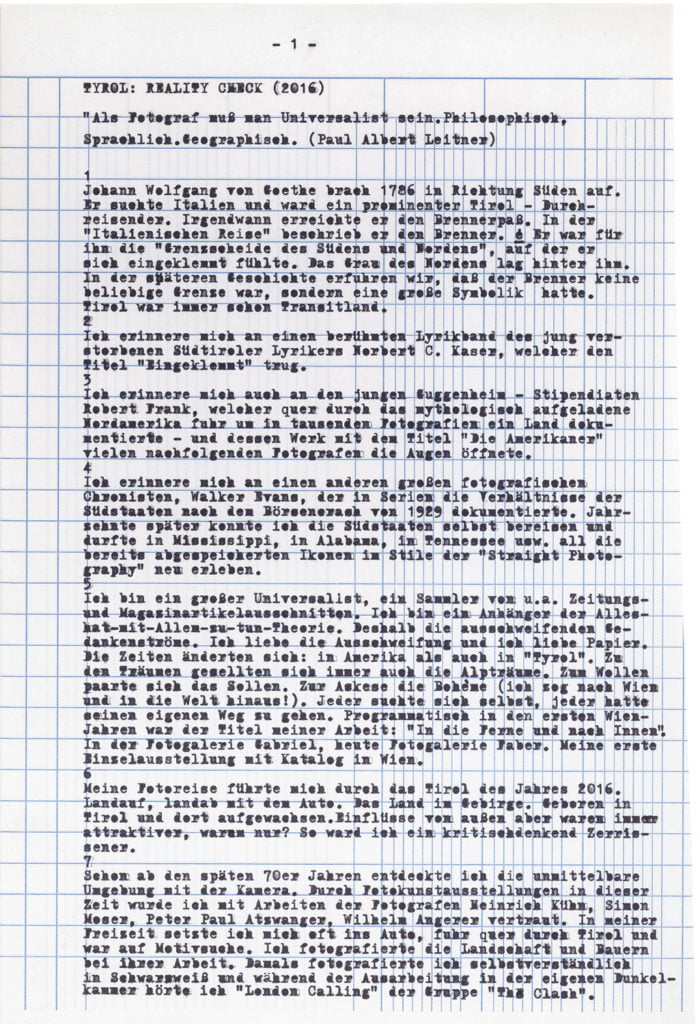

Under his gaze, what is close to us becomes strange and unfamiliar, and the familiar remote; what seems real becomes unreal, and what appears unreal is transformed into reality. He shows us ‘his Tyrolean world’ in its – as he sees it – absurd structure, fascinating images of a comprehensive Leitneresque theatrum mundi. We have the photograph of a shabby, faded boundary demarcation for the Brenner border crossing that was once mythically charged and is (now once again) politically explosive; we have the absurd landscapes of fences slicing through the countryside, sealing off the private from a now estranged world perceived as dangerous; we have Leitner’s vistas taken from hotel rooms onto a landscape that seems to outdo its own clichés; we have the rusting wrecks of American road cruisers heralding the end of the American dream – reflections one and all of his obsessive and surreal view of the world, visual sketches, fragments, imaginings from the travel journal of a possessed image-maker, armed with which he finds himself tracking down the transformations of the world and his own self. What better way to depict the irony and madness of everyday life.

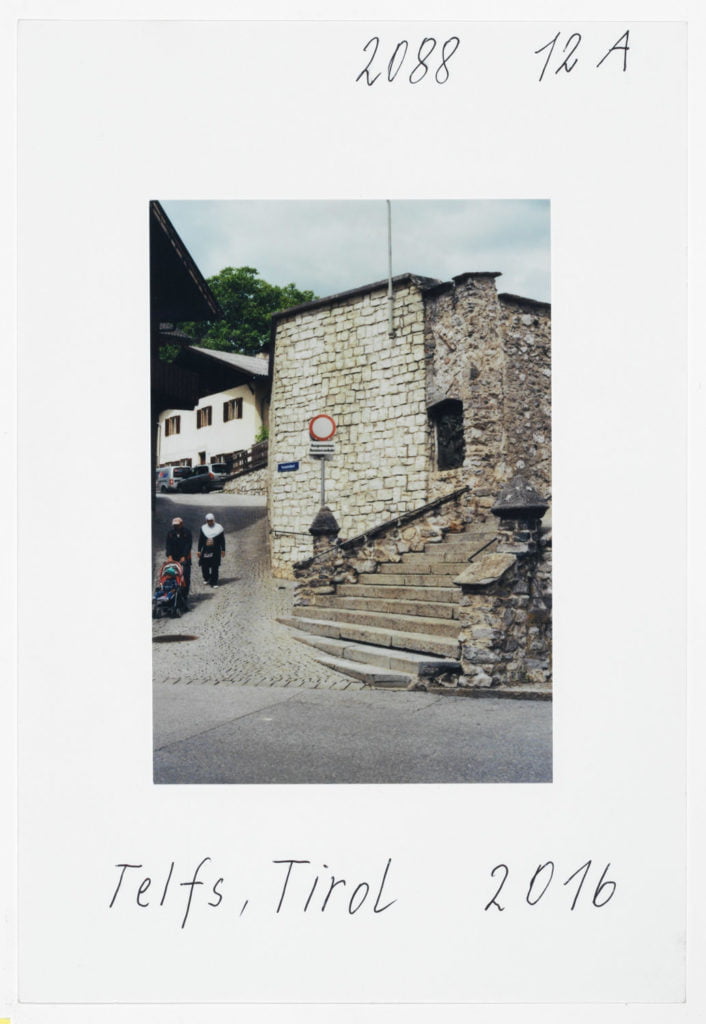

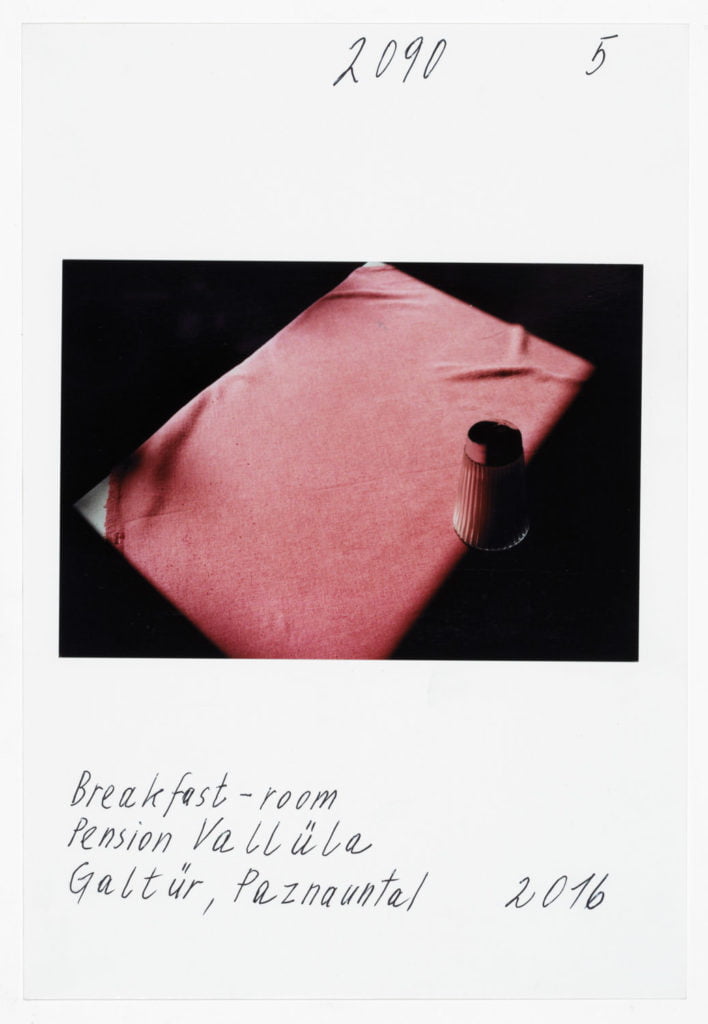

When he portrays two Muslims in front of the church in Telfs, the woman in a headscarf, the man pushing a stroller, it’s as if he is paraphrasing well-known Tyrolean tropes by Alfons Walde. At first glance it’s as if we are in a Bosnian village somewhere. At a B&B in Galtür it’s a sugar shaker on a table that has caught his eye. Leitner’s references to American photographers such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore are clear.

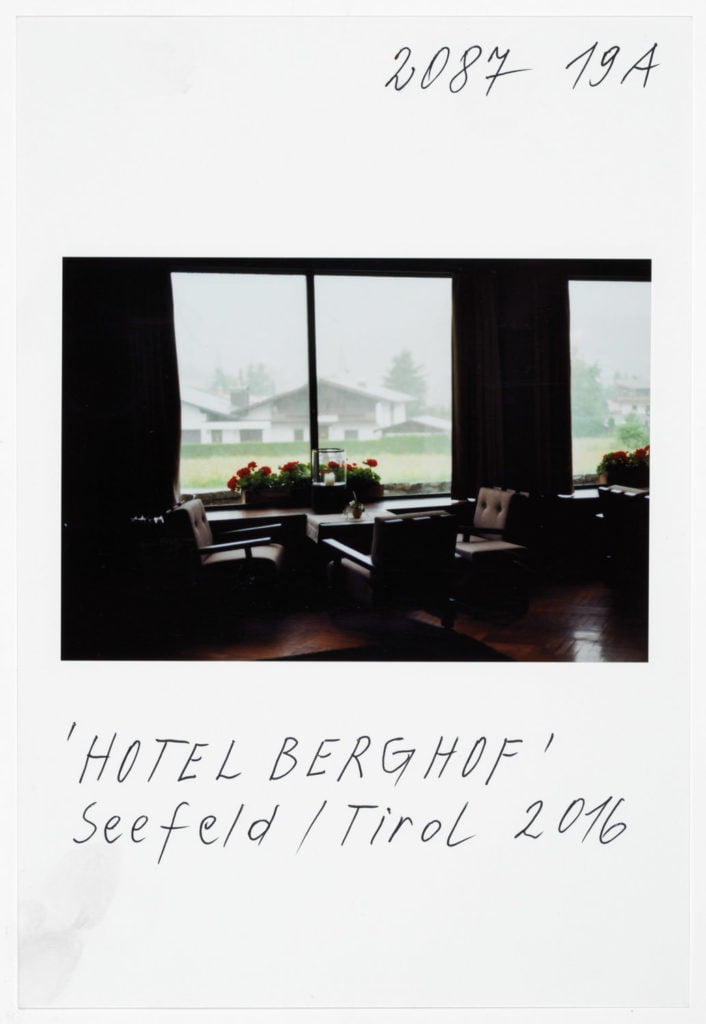

At Hotel Berghof in Seefeld, a landmark of alpine Bauhaus architecture, the traveller’s gaze appears to linger on the elegant interior before returning to the world outside, beyond the panoramic window; no look back in anger, but one filled with empathy. The Tyrolean photographs combine into an oeuvre of astounding and ever expanding diversity. As exuberant and unfathomable as it may now be, with a profusion over which Leitner seeks in vain to gain control through systematic classifications, groupings and themes, his work is nonetheless borne by a consistent artistic approach, a way of working and thinking which he himself has expressed in a number of phrases. It is certainly worth quoting and interpreting some of Leitner’s key programmatic comments here. First and foremost, a core statement by Leitner on the pace at which he works and lives his life, specifically: ‘The best pace for a photographer is walking pace.’ Indeed, Leitner is the flâneur among photographers; any haste is alien to him; he lets himself drift as he sets off in search of motifs. In Tyrol he covered 671 km in a hired car to do his on-site ‘photo rounds’, as he calls them. Leitner ‘be-strides’ his world, hours and days at a time, wherever he happens to be. His work method is based on slowness and exactness. For someone hot on the heels of the serendipitous, he takes his time. He once quoted Hartmut Böhme in an interview: ‘The flâneur does not pick the fastest route from A to B; he much prefers the odysseys of pure chance.’[ref]Hartmut Böhme, Schildkröten spazieren führen, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, May 19th, 2007, online: http://www.nzz.ch/articleF2LNV-1.361104. [/ref] Of course, it goes without saying that commercial constraints, commissions, purposes, and schedules are completely alien to him, just as he has no interest whatsoever in the swiftness and arbitrariness of digital photography. With his belief in the uniqueness of an image, his world has remained analogue to this day. He makes his decisions before and during the photograph; he selects his images meticulously while photographing, not afterwards. What’s crucial is the right moment, the right motif at the right time. On his field trips Leitner is always on the lookout, his timing’s right; indeed, another one of Leitner’s core statements is that ‘what comes after is not like what came before’.

For Leitner, to take a photograph is to ‘take an attitude’. With Leitner, that also means having an attitude, a stance. Leitner also says, ‘it’s all much of a muchness with me’. His world is a dazzling kaleidoscope bursting with sensations and inspirations; he loves quotations, objects, images in often surprising and ironic contexts; he wants to combine them, fuse them into a harmonious and cohesive cosmos; for Leitner, art and life are as one, and if life does go on, then it does so in his images.

Gerald Matt, born in 1958 in Hard, Vorarlberg, works as a freelance curator and cultural manager.